Table of contents

Active customer count

Founders don't usually get surprised by revenue when they're watching it closely. They get surprised by who the revenue is coming from: fewer customers paying more, many customers paying less, or a quiet leak of logos that pricing temporarily hides. Active customer count is the quickest way to see that shift before it becomes a strategy mistake.

Active customer count is the number of unique customer accounts that are currently "active" based on your definition (typically: paying customers with an active subscription or access entitlement) at a specific point in time or within a period.

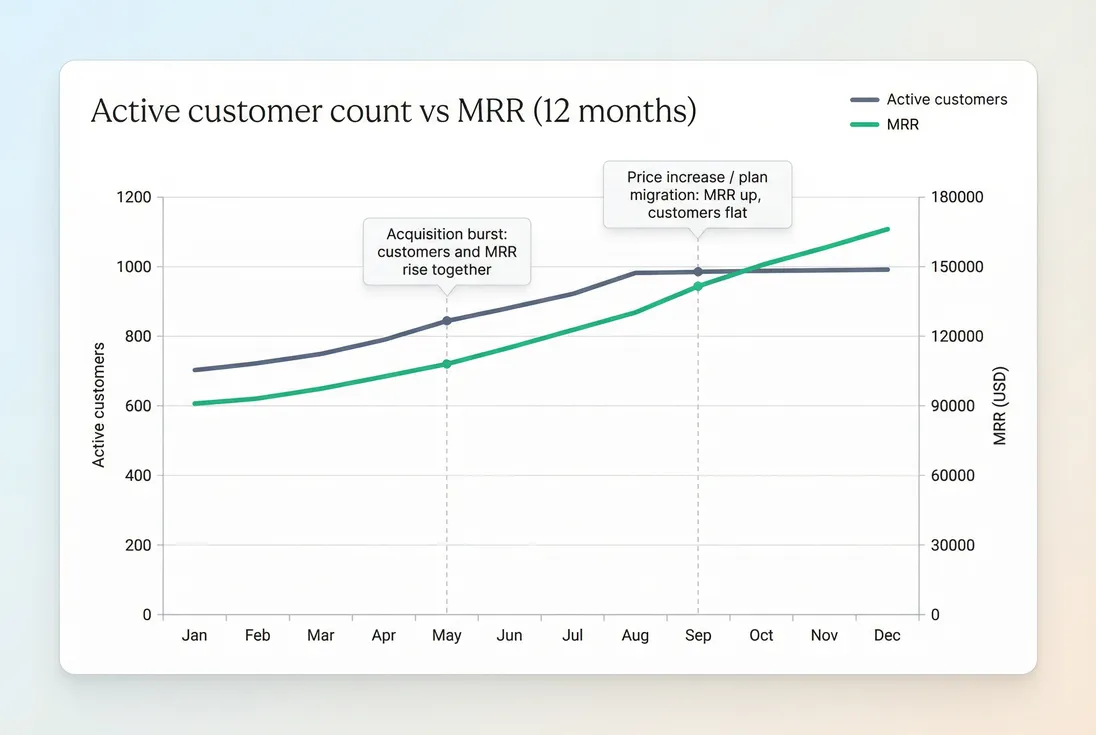

Tracking active customers alongside MRR shows whether growth is coming from more logos or more revenue per logo—two very different businesses operationally.

What counts as "active"

This metric sounds simple until you run into edge cases. You need a definition that matches how your company behaves operationally (access, support load, renewal responsibility) and financially (what you consider a customer you "have").

Common definitions founders use:

Point-in-time active (most common)

"How many active paying customers do we have today (or at month-end)?"

Use this when you care about current footprint, retention, and capacity planning.

Period active (useful for product/CS load)

"How many customers were active at any point during the month?"

Use this when you care about total customers touched by onboarding, support, infra, or customer success work in a period.

Practical inclusion rules

Most SaaS teams end up with rules like these (adjust to your model, but write them down):

- Trials: usually excluded (they inflate customer count without contractual commitment). If you want to track trials, use a separate funnel metric like Free Trial.

- Canceled but still has access (end-of-term): typically included until access ends (especially for month-end reporting).

- Delinquent / failed payment: depends on whether you cut off access. If access continues, include them but monitor separately (involuntary churn risk). If access stops, exclude.

- Paused subscriptions: typically excluded because they are not receiving service (but track pauses explicitly).

- Annual prepaid: included throughout the paid term (they are customers even if cash timing differs from monthly billing).

- Multiple subscriptions per customer: count the customer once. Active customer count is a logo measure, similar in spirit to Logo Churn.

The Founder's perspective: If "active" doesn't match who can log in and who your team must support, the metric will mislead you on hiring, onboarding load, and churn urgency—even if finance thinks the number is "correct."

How to calculate it consistently

Active customer count becomes reliable when you make two decisions: (1) unit of counting and (2) time cut.

Step 1: Decide the unit (customer, account, organization)

In B2B SaaS, "customer" usually means an account/company. In B2C, it might be an individual. The key is to avoid mixing levels.

- If one company has 300 seats, it is still one active customer.

- If you sell through resellers, decide whether the reseller is the customer or the end-client is the customer. Pick one and be consistent.

Step 2: Use a stable time cut

For reporting, founders typically use end-of-month to align with MRR and churn views:

- Month-end active customer count pairs cleanly with MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and retention reporting.

- Daily active customer count is useful for operational dashboards, but it will be noisier.

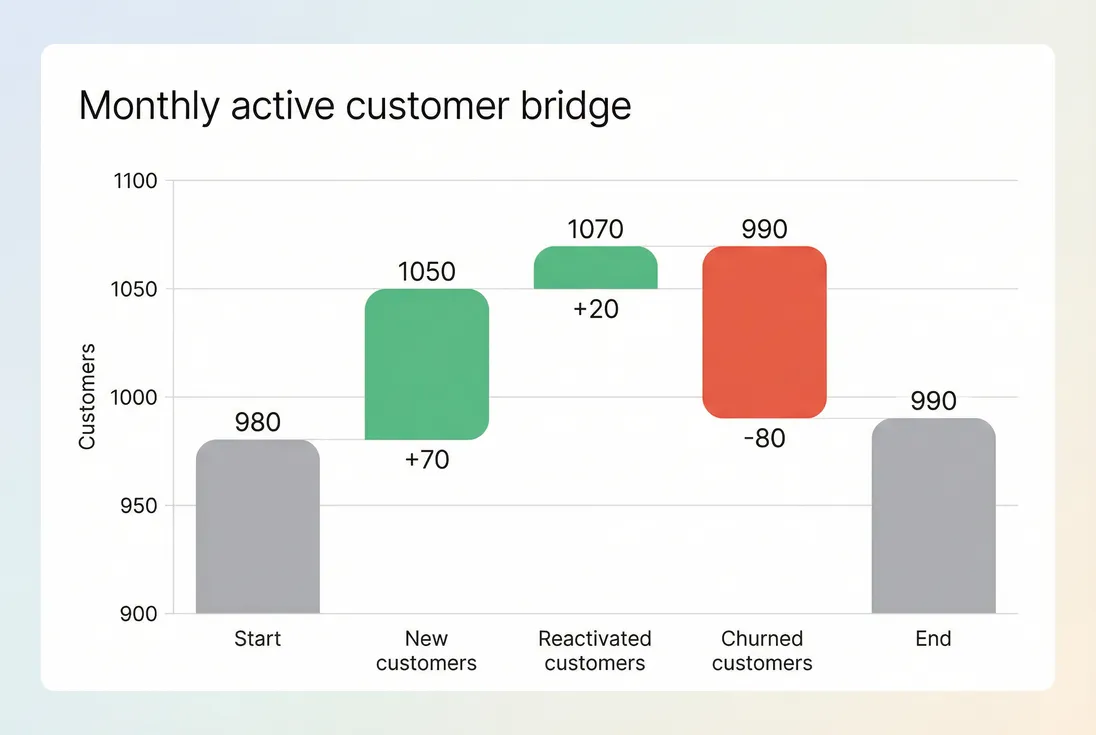

The movement equation (why it changes)

A helpful way to operationalize the metric is to treat it like a balance:

This equation is simple, but it forces the right questions:

- Are we adding enough new customers?

- Are we seeing meaningful reactivations (win-backs)?

- Is logo churn erasing growth?

If you want to go deeper on the churn side, pair this with Customer Churn Rate and Logo Churn.

A monthly bridge makes "flat customers" explainable: you can see whether it's weak acquisition, elevated churn, or both.

What this metric reveals

Active customer count is a "shape of the business" metric. It tells you what kind of engine you're building and what will break first.

1) Whether growth is customer-led or price-led

MRR can grow while customers stay flat (or even decline). That can be healthy—if deliberate.

A useful relationship:

So if MRR is rising but active customers are not, you're relying on ARPA growth. Use ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) to validate what's happening.

2) Whether churn is being masked

Discounts expiring, price increases, or expansion can hide logo churn for a while. Active customer count "unhides" it.

If active customers trend down for 2–3 months:

- your pipeline may be weaker than revenue implies,

- your churn problem is real even if MRR looks stable,

- your support burden may drop temporarily, but your growth ceiling is shrinking.

3) Whether you're changing your ICP (intentionally or accidentally)

A flat or declining customer count with rising MRR is often an early sign of moving upmarket. That has second-order effects:

- longer sales cycles (watch Sales Cycle Length),

- higher concentration risk (watch Customer Concentration Risk),

- different onboarding and success motion.

The Founder's perspective: If you're moving upmarket, you should see customer count flatten and churn behavior improve in the remaining base. If customer count flattens because SMB churn is rising, you're not moving upmarket—you're leaking.

What drives changes month to month

Active customer count moves for a handful of reasons. The key is learning to diagnose which one is dominant, fast.

New customers (acquisition)

This is influenced by:

- lead flow and conversion (see Lead Conversion Rate),

- sales execution (see Win Rate),

- trial-to-paid performance (see Free Trial).

A useful founder habit: compare net new customers vs new customers. If net is weak despite decent gross adds, churn is the culprit.

Churned customers (logos lost)

Customer count is directly sensitive to churn, which means it's often the fastest "red flag" metric—especially in SMB.

To understand why you're losing customers, you'll eventually need:

- churn reasons (see Churn Reason Analysis),

- retention by cohort (see Cohort Analysis).

Reactivations (win-backs)

Reactivations can indicate:

- churn was driven by temporary conditions (budget freezes, seasonality),

- your product has episodic value,

- your cancellation flow is too "easy" without intervention.

Don't over-celebrate reactivations unless the reactivated cohort retains better than before.

Billing artifacts (not real demand)

Some changes are definitional rather than behavioral:

- Payment failures: if you cut off access quickly, active customer count will dip even if customers "intend" to stay. Track involuntary churn separately (see Involuntary Churn).

- Refunds and chargebacks: depending on policy, customers may be removed from "active" counts. See Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS.

- Collections: enterprise customers can be active while invoices age. If your definition uses "paid" instead of "entitled," reconcile with Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging.

How to interpret changes correctly

Raw customer count changes are easy to misread. Use these interpretation patterns to avoid false conclusions.

When customer count rises

This usually means acquisition is working and churn is under control—but verify mix:

- Are the new customers your target segment?

- Are they sticking past onboarding?

Pair the lift with early retention signals like Onboarding Completion Rate and cohort retention.

When customer count is flat

Flat can mean "stable and efficient" or "stalled."

Diagnose with the bridge logic:

- gross adds are fine but churn is high (a retention problem),

- gross adds are low but churn is normal (a top-of-funnel or sales efficiency problem),

- both are mediocre (your GTM message or ICP may be off).

When customer count falls

Assume urgency until proven otherwise. Common causes:

- a broken onboarding path,

- a product issue causing accelerated churn,

- a pricing/packaging change that pushed out low-end customers.

If the decline coincides with a pricing move, validate whether it was intentional (moving upmarket) by checking whether MRR concentration increased and whether churn stabilized among the remaining base.

Customer count vs MRR: a quick read table

| Active customer count | MRR trend | Usually means | Founder action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up | Up | Healthy acquisition + retention | Scale acquisition carefully; protect onboarding |

| Flat | Up | ARPA rising (upsell, price, mix) | Check ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) and concentration risk |

| Up | Flat/Down | Lower pricing, downgrades, heavy discounting | Review Discounts in SaaS and contraction drivers |

| Down | Flat/Up | Losing logos but offset by expansion/price | Investigate churn reasons; strengthen retention motion |

| Down | Down | Broad churn and weak acquisition | Treat as priority 0; focus on retention + pipeline |

The Founder's perspective: The most dangerous pattern is "customers down, MRR up." It feels like progress, but it can quietly turn you into a high-risk, high-concentration business without the sales org maturity to support it.

Where this metric breaks

Active customer count fails when "customer" and "active" aren't cleanly defined in your systems.

Multi-entity and hierarchy issues

If a parent company has multiple child accounts:

- Counting at the wrong level can swing customer count wildly during consolidations.

- Decide whether "customer" maps to billing entity, workspace, or legal entity—and stick to it.

Plan migrations and grandfathering

A plan migration can create artifacts:

- duplicate customer records,

- temporary pauses,

- unusual proration behavior.

Always reconcile "active customers" against your billing source of truth and verify uniqueness.

Usage-based and hybrid models

In Usage-Based Pricing, customers might have:

- an active contract but zero usage (still a customer),

- usage without a recurring subscription line item (still active if entitled).

Define active based on entitlement, not whether a usage invoice happened to be generated in the period.

Free plans and freemium

If you have a free tier, don't mix:

- active customers (paying),

- active accounts (including free),

- active users (engagement).

Track engagement with Active Users (DAU/WAU/MAU) separately. Mixing these is one of the fastest ways to make churn and retention discussions incoherent.

How founders use it in decisions

This metric earns its keep when it drives concrete actions—not when it's a vanity graph.

Capacity planning (support, success, infra)

Active customers is a proxy for:

- number of accounts that can file tickets,

- number of renewals to manage,

- breadth of onboarding work.

If you're hiring in CS or support, customer count is often more predictive than MRR in SMB (tickets scale with logos). In enterprise, MRR might dominate because account complexity scales with contract size—so segment by tier.

GTM focus and sequencing

Customer count helps you answer:

- Are we scaling acquisition or patching retention?

- Is our current motion consistent with our pricing?

For example, if customer count growth is strong but MRR growth is weak, you may be underpricing or over-discounting (see ASP (Average Selling Price)). If MRR is strong but customer count is weak, you may be drifting upmarket without the sales motion to sustain it.

Early warning for retention problems

Because it's a logo metric, active customer count can flag churn problems before they show up as a big revenue decline—especially when expansion offsets churn.

Pair it with:

- Retention concepts,

- Cohort Analysis to see whether newer cohorts retain worse,

- churn reason review to learn what changed operationally.

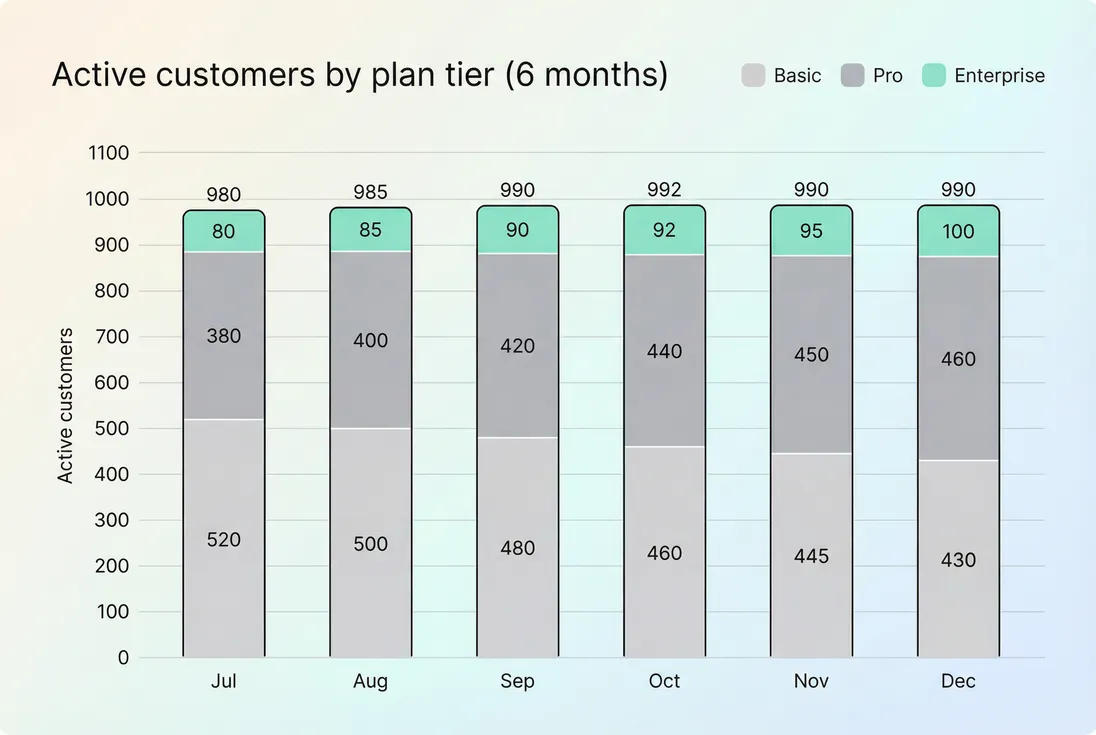

Segmentation that actually helps

Active customer count is most useful when you can break it down by:

- plan tier,

- acquisition channel,

- geography,

- cohort (signup month),

- customer size bucket.

A flat total can hide a major mix shift: losing low-tier customers while higher tiers grow changes support load, churn profile, and future expansion potential.

If you're using GrowPanel to investigate changes, features like the customer list, mrr movements, and filters help you isolate which segment drove the shift (for example, a specific plan or cohort) and validate whether the movement came from churn, upgrades, or reactivations.

A simple operating cadence

For most founders, this cadence is enough to keep customer count actionable:

- Weekly (SMB/PLG): review net customer adds and logo churn signals; look for sudden drops that indicate onboarding or billing issues.

- Monthly (all models): run the customer bridge (start, new, reactivated, churned, end) and compare to MRR and ARPA.

- Quarterly: segment by cohorts and tier to ensure you're not growing through a leaky bucket.

Tie the review to decisions:

- If churn is driving flat count, prioritize retention work and onboarding improvements.

- If new adds are the limiter, fix demand gen, targeting, or sales execution.

- If customer count declines while MRR rises, explicitly decide whether you're comfortable with the implied move upmarket—and manage concentration risk accordingly.

Key takeaway

Active customer count is the cleanest check on whether you're building a bigger customer base or just extracting more revenue from a shrinking one. Track it consistently, explain changes with a monthly bridge, and always read it alongside MRR and ARPA to avoid being fooled by pricing, expansion, or billing artifacts.

Frequently asked questions

There is no universal benchmark because it depends on pricing and segment. Fifty active customers at 2,000 ARPA can be healthier than 500 customers at 50 ARPA. Focus on trend quality: steady net adds, stable logo churn, and improving payback.

That usually means you are moving upmarket or expanding accounts faster than you are losing logos. It can also be a pricing increase, packaging change, or fewer discounts. Check ARPA movement and customer concentration risk so growth is not dependent on a few large accounts.

Only if your definition matches how you run the business. Most teams exclude trials, include customers with paid access through period end, exclude paused accounts, and treat delinquent accounts separately until access is removed. Document the rules and keep them consistent for trend comparability.

Weekly is useful for fast-moving SMB or PLG motion; monthly is sufficient for sales-led or enterprise. Review it alongside logo churn and new acquisitions so you can explain the net change. When it diverges from MRR, investigate ARPA and plan mix.

Use it to plan support and success capacity, validate GTM scaling, and catch churn problems earlier than revenue-only views. Pair it with cohorts to see if newer customers retain worse, and with AR aging to spot whether collections or payment failures are distorting "active" status.