Table of contents

Contraction mrr

Contraction MRR is where "we didn't lose the customer" can still mean "we lost meaningful growth." A few large downgrades can quietly erase weeks of new bookings, distort your forecasts, and force your team to "run faster just to stay in place."

Contraction MRR is the monthly recurring revenue you lose from existing customers who remain customers but pay less than before (downgrades, fewer seats, removed add-ons, lower billable usage tier).

What contraction MRR actually includes

Contraction MRR is only the recurring revenue decrease from customers who were already paying you and then reduce their commitment. Or in the case of changing from monthly to yearly billing, an increase in commitment, but still an MRR contraction.

Typical contraction events:

- Seat reductions (per-seat pricing)

- Plan downgrades (Pro to Basic)

- Billing interval change (Month to year) - which is actually increasing their commitment

- Removing paid add-ons (security pack, extra workspace)

- Renewal "right-sizing" downward (same customer, smaller contract)

- Usage dropping into a lower priced band (for usage-based models that translate into a lower recurring baseline)

What contraction MRR is not:

- Full cancellations (that's churn; see MRR Churn Rate and Logo Churn)

- New sales (see MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue))

- Reactivations (see Reactivation MRR)

- One-time credits or refunds (those are billing events; handle separately from recurring metrics)

A useful mental model: churn is losing the relationship; contraction is losing the footprint. The interventions, and the teams involved, are often different.

The Founder's perspective

If churn is high, you have a retention fire. If contraction is high, you may have a value, packaging, or "economic buyer" problem—even if your retention looks decent on the surface.

How it is calculated

At its simplest, contraction MRR is the sum of all MRR decreases from existing accounts during a period, excluding cancellations.

A clear way to express it:

Many teams also track a contraction rate so it's comparable across months:

A concrete example

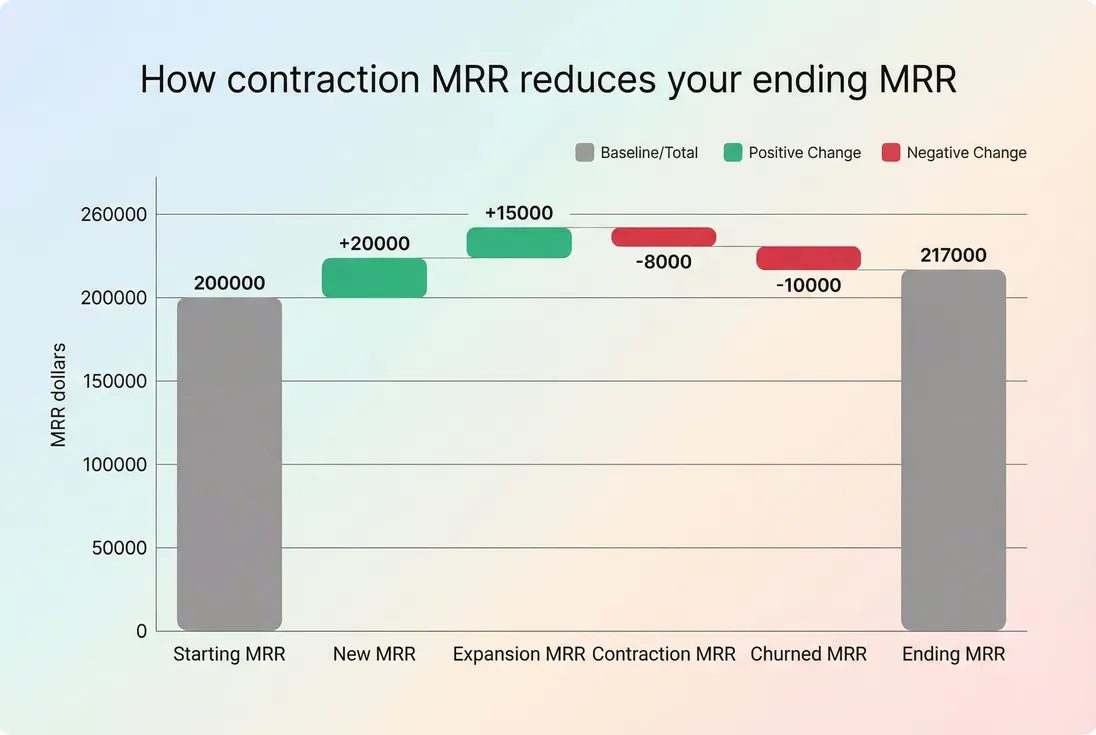

Suppose you start April with $200,000 MRR.

During April:

- 12 customers downgrade for a total of $8,000 contraction MRR

- 6 customers expand for $15,000 expansion MRR (see Expansion MRR)

- 10 customers cancel for $10,000 churned MRR

- You close new business for $20,000 new MRR

Ending MRR:

So: 200,000 + 20,000 + 15,000 − 8,000 − 10,000 = 217,000 ending MRR.

Avoiding double counting

A common reporting pitfall is counting both contraction and churn for the same customer in the same period (downgrade early in the month, cancel later).

Two practical rules that keep reporting clean:

- End-state rule (simple): if the customer is active at period end, treat the net decrease as contraction; if not active, treat it as churn.

- Single-loss rule (more precise): for each account, ensure total negative movement in a period never exceeds its starting MRR.

If you want contraction to drive decisions, consistency matters more than philosophical purity.

What this metric reveals

Contraction MRR is an early-warning signal for revenue retention problems because it usually shows up before logos leave. In practice, it answers five founder-relevant questions.

1) Are customers "right-sizing" away from you?

A stable logo base with rising contraction typically means customers still need something from you, but not as much as you sold.

Common patterns:

- Seats purchased for rollout that never happened

- Add-ons sold during procurement that never got adopted

- Plans bundled with features the customer doesn't value

This is where Feature Adoption Rate and onboarding metrics (like Time to Value (TTV)) become leading indicators: low adoption often precedes downgrades.

2) Is your pricing model amplifying volatility?

Contraction behaves differently by pricing model:

| Pricing model | Typical contraction drivers | What "good" looks like |

|---|---|---|

| Per-seat | layoffs, seasonal staffing, over-seating at rollout | contraction concentrated in smaller accounts, not your best-fit segment |

| Tiered plans | customers drop features, downgrade at renewal | downgrades are rare and tied to clear segmentation (not widespread dissatisfaction) |

| Usage-based | real usage decline, budget controls, product replaced | predictable seasonality and strong rebound; expansion offsets contraction over time |

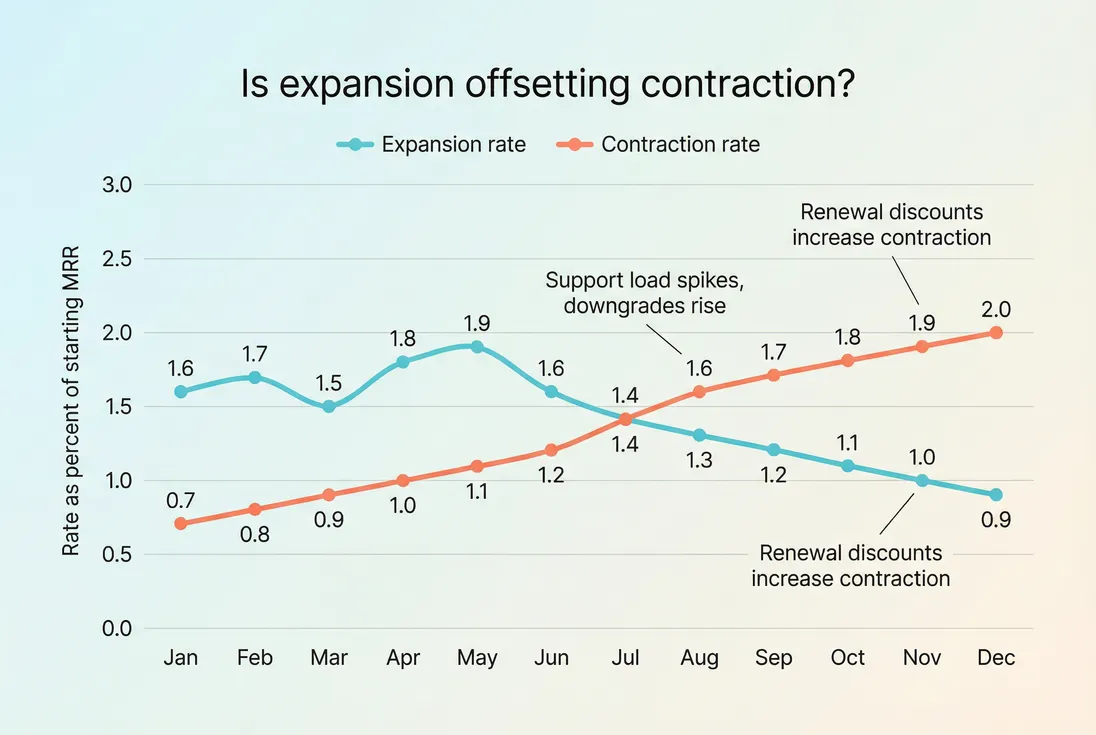

If your product is usage-sensitive, you should expect more contraction—but you should also design strong expansion mechanics. Track contraction alongside NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention).

3) Is contraction hiding inside discounts?

Many contraction events are not explicit downgrades; they're "commercial concessions":

- A renewal discount to prevent churn

- Removing an add-on "temporarily"

- Dropping price per seat to match a competitor

These still reduce recurring revenue going forward. If discounts are driving contraction, treat it as a pricing and positioning problem (see Discounts in SaaS, ASP (Average Selling Price), and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account)).

The Founder's perspective

If contraction is mostly discount-driven, your churn might look "managed," but you're paying for retention by giving away margin and growth. That's usually fine for a quarter. It's dangerous as a strategy.

When contraction MRR becomes a growth killer

Contraction becomes existential when it changes the math of growth efficiency. Every dollar of contraction has to be replaced by:

- more new MRR (which increases CAC pressure), or

- more expansion MRR (which requires real product value), or

- both

That's why contraction flows directly into metrics founders use for capital planning like Burn Multiple and SaaS Magic Number: if contraction rises, you need more sales and marketing output to achieve the same net growth.

Practical red flags to watch

Contraction exceeds expansion for multiple months

This is a retention/product signal, not a sales execution issue.Contraction clusters in your "best-fit" segment

Example: your mid-market cohort is shrinking seats. That often points to missing enterprise readiness, weak integrations, or ROI not being proven.Contraction concentrates in recent cohorts

New customers downgrading within 60–120 days often means poor onboarding, mis-sold expectations, or packaging misalignment. Use Cohort Analysis to confirm.A few large accounts drive most contraction

That's a customer concentration issue in disguise. Cross-check with Customer Concentration Risk and Cohort Whale Risk.

How founders should interpret changes

If contraction rises suddenly

Treat a sudden spike like an incident and run a fast root-cause pass:

Commercial checks

- Did you change packaging or introduce a cheaper tier?

- Did a competitor launch a visible alternative?

- Did your team push heavy discounting this month?

Customer checks

- Are downgrades concentrated in one industry (budget shock)?

- Are they concentrated in one plan (feature/value gap)?

- Are they concentrated among customers with a specific integration (breakage)?

Product checks

- Was there an outage or major reliability issue? (See Uptime and SLA)

- Did a key workflow regress?

- Did activation or onboarding completion drop? (See Onboarding Completion Rate)

A useful triage output is a simple breakdown: contraction by plan, segment, cohort month, and reason category. If you have clean reason capture, pair this with Churn Reason Analysis.

If contraction trends up gradually

A gradual increase is usually more dangerous than a spike because it suggests a structural drift:

- Your product is becoming easier to "use less"

- Your champion is losing internal influence

- Your pricing metric is misaligned with value (customers can reduce usage without losing value)

This is where you revisit:

- value metric alignment (see Usage-Based Pricing and Per-Seat Pricing)

- packaging fences (what prevents "downshift then coast"?)

- proof of ROI and adoption milestones

If contraction falls sharply

Don't celebrate blindly. A contraction drop can mean:

- improved product adoption and stickiness (good)

- customers are churning instead of downgrading (bad)

- contraction is being masked by accounting/reporting changes (bad)

Always check the companion metrics:

- Net MRR Churn Rate (net of expansion and contraction)

- MRR Churn Rate

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

How to use contraction MRR in real decisions

Forecasting and capacity planning

Contraction is one of the most under-modeled parts of revenue forecasting. Many early-stage teams forecast:

- new MRR

- churned MRR

…and implicitly assume the rest is stable. When contraction is meaningful, that assumption breaks.

A practical approach:

- Forecast churned MRR using recent average and seasonality.

- Forecast contraction MRR separately using a trailing average and segment adjustments.

- Validate against leading indicators (support load, adoption, renewals at risk).

If contraction is rising, treat it like a growth tax: you'll need more pipeline to hit the same target (see Qualified Pipeline and Win Rate).

Packaging and pricing decisions

Contraction data is brutally honest about whether your packaging matches value:

- If most contraction is "remove add-on," the add-on may be hard to adopt or overpriced.

- If most contraction is "downgrade tier," your tier differentiation may be weak.

- If most contraction is "seat reductions," you may need stronger per-seat value or a different value metric.

This is also where Price Elasticity thinking helps: contraction is one way elasticity shows up after customers are already acquired.

Customer success playbooks

Contraction is often preventable with earlier intervention:

- Identify "seat slide" accounts: seats purchased vs active users (see Active Users (DAU/WAU/MAU))

- Trigger a success review before renewal if utilization is dropping

- Introduce expansion paths that are operationally easier than downgrading (e.g., add-ons that actually deliver value)

The Founder's perspective

When contraction rises, I don't ask my team to "upsell harder." I ask: which customers are shrinking, what value are they not getting, and what in our product or packaging makes shrinking the easiest choice?

Measurement best practices that prevent confusion

Define "effective date" of contraction

Make sure your team agrees on when a downgrade counts:

- when the customer requests it

- when the billing change takes effect

- when usage drops below a threshold

Whatever you choose, keep it consistent month to month so trends are real.

Separate operational and reporting views

Operationally, you may want to see every event (downgrade then churn). For reporting, you want clean categories that reconcile.

If you use GrowPanel reporting, the most practical workflow is to review revenue changes in MRR movements and then slice the drivers with filters:

(You're looking for concentration by plan, country, channel, or customer list—whatever matters to your business.)

Reconcile with ARPA and customer counts

Contraction can be "invisible" if customer count is growing. Always pair it with:

If customers are up but ARPA is down, contraction (or discounting) is often the culprit.

Benchmarks and what "good" means

Contraction benchmarks vary by segment and model, but these rules of thumb are directionally useful:

- Early-stage SMB SaaS: contraction under ~1% of starting MRR per month is often fine if expansion is healthy.

- Mid-market SaaS: target under ~0.5–0.8% per month; downgrades should be the exception, not the norm.

- Enterprise SaaS: contraction should be relatively rare month to month; when it happens, it's usually a renewal re-scope that should be explainable account by account.

More important than the absolute number:

- Is contraction predictable?

- Is it offset by expansion?

- Is it concentrated in a segment you care about?

A simple contraction MRR "debug" checklist

Use this when contraction surprises you:

- Quantify: contraction MRR, contraction rate, and top accounts by contraction.

- Classify: seat loss vs tier downgrade vs add-on removal vs discounting.

- Localize: segment, plan, cohort month, and industry.

- Explain: top 10 accounts—write the human story for each.

- Act: pick one lever (product adoption, packaging, success play, pricing guardrails) and run it for 30 days.

If you can't explain contraction in plain English, you can't fix it.

Related metrics to read next

- Expansion MRR

- MRR Churn Rate

- Net MRR Churn Rate

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention)

- GRR (Gross Revenue Retention)

Frequently asked questions

Contraction MRR is revenue lost from existing customers who stay subscribed but pay less (downgrade, fewer seats, lower usage tier). Churned MRR is revenue lost from customers who cancel entirely. Founders separate them because the fixes differ: contraction usually needs packaging and value delivery, churn often needs retention and win-back.

For many B2B SaaS businesses, contraction should be materially lower than expansion. As a rough guide, contraction under about 1 percent of starting MRR per month is healthy for SMB SaaS, and under about 0.5 percent for mid-market and enterprise. If contraction regularly exceeds expansion, net retention will struggle.

Yes. Seat-based and usage-based products often see predictable downshifts after peak periods (holidays, tax season, annual events). It is acceptable if it is expected, forecastable, and rebounds. The danger is structural contraction: steady seat shrinkage, chronic downgrades after onboarding, or contraction concentrated in your best-fit segment.

Pick a consistent rule to avoid double counting. Many teams classify the final state at period end: if the account is active, count contraction; if it is canceled, count churn. Operationally, track both events in your CRM or billing notes, but reporting should ensure each dollar of starting MRR is lost once.

The big drivers are seat reductions, downgrades to cheaper plans, removing add-ons, discounts granted at renewal, and usage dropping below thresholds in usage-based pricing. Root causes usually map to value gaps, weaker product adoption, budget cuts in a segment, or pricing and packaging that encourages downgrades instead of right-sizing.