Table of contents

Customer payback period

Customer payback period is one of the fastest ways to tell whether "growth" is creating value or just converting cash into busy work. If payback is long, every new customer can increase risk by consuming runway before they fund the next hire, campaign, or product milestone.

Customer payback period is the number of months it takes for the gross profit generated by a customer to cover the cost to acquire that customer (and, in many teams, the direct costs to onboard and activate them).

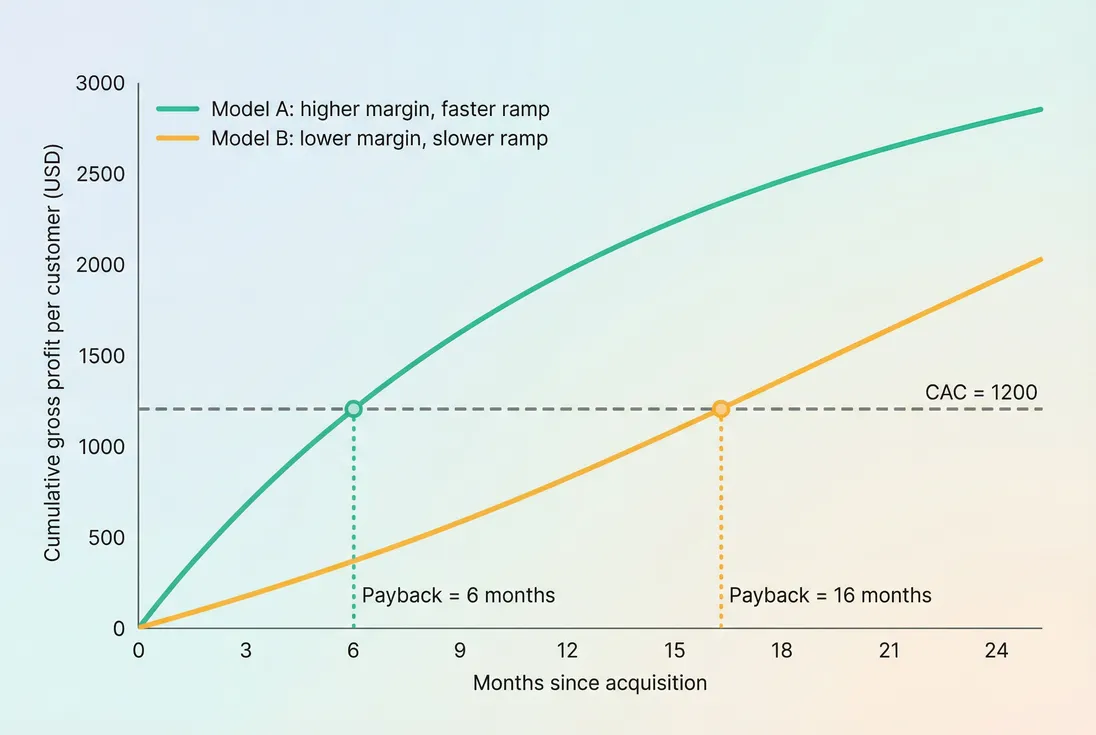

Payback is the month where cumulative gross profit crosses CAC; two businesses with the same CAC can have very different payback based on margin and ramp.

What payback reveals

Payback answers a practical founder question: How long does each new customer "borrow" cash from the business before they start funding growth?

It's easy to celebrate new ARR and pipeline. Payback forces you to reconcile growth with timing:

- Long payback pushes you toward raising capital, slowing hiring, or shifting to annual contracts.

- Short payback gives you permission to scale sales and marketing with less cash stress.

- Worsening payback is often an early warning signal—especially if top-line growth still looks fine.

Payback also complements other unit economics metrics:

- It's the time-based counterpart to LTV (Customer Lifetime Value) and LTV:CAC Ratio.

- It ties directly into burn planning alongside Burn Rate and Burn Multiple.

- It should be validated with retention reality via Cohort Analysis and churn metrics like Logo Churn and Net MRR Churn Rate.

The Founder's perspective

If payback is 18 months and your runway is 12, you're not "scaling"—you're accumulating obligations your cash balance can't survive. The fix might be pricing, margin, or sales efficiency, but the decision starts with admitting the timing mismatch.

How to calculate it correctly

Most payback confusion comes from (1) using revenue instead of gross profit, and (2) mixing "cash received" with "economic value delivered."

The core formula

At its simplest:

And monthly gross profit per customer is commonly estimated as:

Where:

- CAC comes from your CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) calculation (usually sales + marketing cost to acquire a customer).

- ARPA is ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account).

- Gross margin reflects delivery costs captured in COGS (Cost of Goods Sold).

This "steady-state" method is acceptable when customers start paying immediately and usage/expansion ramps quickly. Many SaaS businesses, however, have ramp periods, discounts, onboarding costs, or delayed go-lives. In those cases, use a cumulative method:

- Build a monthly series of gross profit per customer after acquisition.

- Cumulate it month by month.

- Payback is the first month where cumulative gross profit ≥ CAC.

That's exactly what the first chart visualizes.

Customer payback vs CAC payback

Founders will hear "payback" used two ways:

- Customer payback period (per-customer view): conceptually about one customer or a representative customer in a segment.

- CAC payback period (blended view): typically computed across all new customers acquired in a period.

They're closely related. The key is consistency in numerator/denominator and segmenting when channel mix changes. If you want the blended metric definition and common SaaS reporting conventions, see CAC Payback Period.

Decide which "payback" you mean

Use two versions intentionally:

1) Economic payback (gross profit payback)

Best for: deciding whether acquisition is fundamentally profitable.

- Uses gross profit over time.

- Ignores timing of cash collection (monthly vs annual prepay).

2) Cash payback (collection payback)

Best for: runway management and financing risk.

- Uses cash collected (net of refunds/chargebacks) relative to acquisition cash outlay.

- Very sensitive to billing terms, annual prepay, and collections.

You don't need perfect accounting to start—but you do need to be explicit which one you're using.

A concrete example

Assume:

- CAC = $1,200

- ARPA = $200 per month

- Gross margin = 80%

Monthly gross profit ≈ $200 × 0.80 = $160

Payback ≈ $1,200 / $160 = 7.5 months

Now consider a discounting change. If you start offering "3 months free" on annual contracts, your CAC might not change, but your early gross profit does—so cumulative payback gets worse even if your steady-state ARPA looks unchanged.

If you run discounts frequently, treat them explicitly (see Discounts in SaaS) and watch downstream effects like Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS.

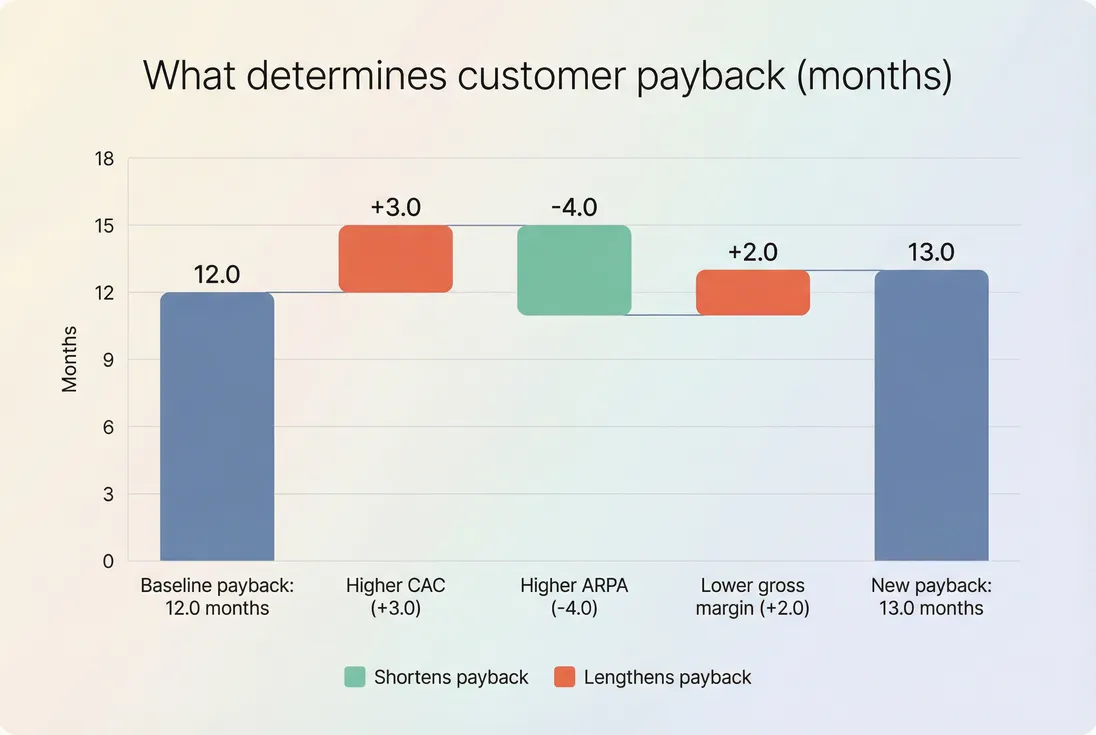

What drives payback up or down

Payback is not a single lever—it's the outcome of several operational systems. That's why it's useful: it forces cross-functional tradeoffs.

Payback moves when CAC, ARPA, or gross margin changes; a "better" payback can hide a worse driver if another driver improved more.

CAC (sales and marketing efficiency)

CAC is usually the biggest swing factor—and the easiest to misunderstand.

Common reasons CAC rises:

- You expand to colder channels.

- You hire ahead of productivity (see Sales Rep Productivity).

- You push upmarket and your Sales Cycle Length increases.

- You add heavy pre-sales support that isn't counted consistently.

If CAC rises but payback stays flat, it often means you also raised price, improved conversion, or shifted mix toward higher ARPA customers. That might be fine—as long as retention holds.

ARPA and pricing quality

ARPA influences payback directly. If customers pay more each month, you repay CAC faster.

ARPA improvements come from:

- Higher list price / packaging

- Better monetization (e.g., per-seat pricing; see Per-Seat Pricing)

- Lower discounting

- More expansion (see Expansion MRR)

A subtle but common failure: raising ARPA by selling customers more than they can adopt. Payback might improve on paper, but churn later erases LTV. Watch retention cohorts and Churn Reason Analysis to ensure ARPA gains are "real."

Gross margin and delivery model

Gross margin is where many SaaS teams accidentally sabotage payback:

- High onboarding/support labor for new customers

- Underestimated infrastructure costs for usage-heavy customers (see Usage-Based Pricing)

- Excessive CSM touches to compensate for product gaps

If your business requires intense early support, your true "month 1–3" gross margin might be much lower than the annual average. In that case, the cumulative method matters.

Ramp time and time-to-value

Even with good ARPA and margin, payback can be bad if customers don't start paying (or don't expand) until late.

Ramp drivers include:

- Free trials and delayed conversions (see Free Trial)

- Implementation lead time (enterprise)

- Slow activation and poor onboarding (see Onboarding Completion Rate and Time to Value (TTV))

This is why founders should avoid calculating payback using only a single "steady" ARPA and margin number if the first few months are structurally different.

The Founder's perspective

If payback is driven by slow ramp—not CAC—you don't fix it by cutting marketing. You fix it by getting customers to value faster: tighter onboarding, clearer activation milestones, and fewer "services disguised as product."

Benchmarks that actually help

A "good" payback depends on your growth motion, retention, and capital strategy. Still, benchmarks are useful for sanity checks.

Here's a practical rule-of-thumb table many founders use:

| Business context | Typical target | When it's a problem |

|---|---|---|

| Self-serve SMB, strong margins | 3–9 months | > 12 months |

| PLG with efficient conversion | 6–12 months | > 15 months |

| Sales-led mid-market | 9–15 months | > 18 months |

| Enterprise with high retention | 12–24 months | > 24 months |

How to interpret this table:

- Short payback is not automatically good if churn is high or growth is capped by a small market.

- Long payback can be rational if retention is exceptional and contracts are long—but it increases financing risk.

To pressure-test, pair payback with:

- Churn Rate (especially early-life churn)

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) for expansion dynamics

- Gross Margin (because payback is a margin story disguised as a sales metric)

When payback gets misleading

Payback is powerful, but easy to game accidentally. These are the failure modes that create bad decisions.

Using revenue instead of gross profit

If you ignore COGS, a services-heavy onboarding model looks great—until you hire the team required to deliver it.

Rule: if a cost scales with customers (support, infra, onboarding labor), it belongs in the payback story one way or another.

Blending segments that behave differently

If you sell to both SMB and mid-market, your "average" payback can be a lie:

- SMB might pay back in 6 months but churn fast.

- Mid-market might pay back in 14 months but retain and expand.

A single blended number makes it hard to choose where to invest. Segment by plan, channel, or ACV band (see ASP (Average Selling Price) and ACV (Annual Contract Value)).

Confusing cash payback with economic payback

Annual prepay can make cash payback look instantaneous. That does not mean your acquisition is efficient—it may simply mean you're borrowing from future delivery obligations.

If you're making hiring decisions, don't rely on cash payback alone. If you're making runway decisions, don't ignore cash payback.

Related metrics that help keep you honest:

- Deferred Revenue

- Recognized Revenue

- Collections friction through Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging

Ignoring churn before payback

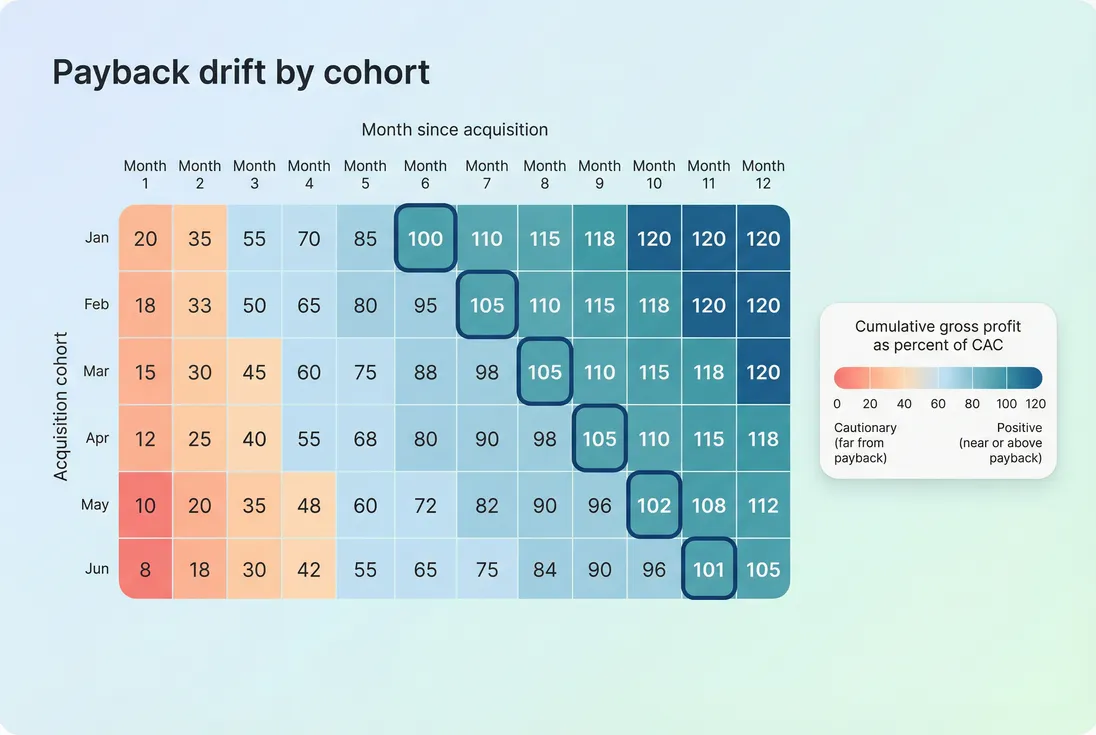

A brutal reality: if a meaningful share of customers churn before the payback month, your modeled payback is not achievable for that segment.

This is why payback should be validated with cohort retention. If you see churn spikes at month 2–3, your effective payback is much worse than your spreadsheet suggests.

Cohort-based payback reveals drift: when newer cohorts take longer to repay CAC, your channel mix, pricing, or funnel efficiency likely changed.

How founders use payback in decisions

Payback becomes valuable when it changes what you do next week—not just what you report.

1) Setting a safe growth pace

Payback is a constraint on how aggressively you can scale. The shorter it is, the less external capital you need to fund growth.

A practical operating rule:

- If payback is short and stable, you can reinvest more confidently.

- If payback is long or volatile, treat growth spend like a balance-sheet decision, not a marketing decision.

This is where payback ties into Runway and Capital Efficiency. If you're trying to reduce burn, payback is often more actionable than a top-line goal.

2) Choosing which GTM motion to emphasize

Payback changes the attractiveness of different go-to-market approaches:

- PLG often wins on shorter payback if conversion and self-serve onboarding are strong (see Product-Led Growth).

- Sales-led motions can justify longer payback if retention and expansion are strong (see Sales-Led Growth).

If you're mid-transition, track payback separately by motion or channel, otherwise you'll misread the trend.

3) Deciding when to raise prices

A pricing change that increases ARPA can shorten payback dramatically—if it doesn't increase churn.

Use payback alongside:

- Price Elasticity

- Renewal Rate

- Retention and churn cohorts

If you want one practical approach: model the payback improvement you expect from a price increase, then set a "maximum acceptable churn increase" that would wipe out the gain.

4) Hiring sales and customer success responsibly

Hiring ahead of revenue is normal—but payback tells you if you're hiring ahead of unit economics.

Examples:

- If payback worsens after hiring AEs, it may be a ramp/productivity issue (not a channel issue).

- If payback worsens after adding CSMs, you may have delivery costs creeping into what used to be a pure software margin profile.

5) Diagnosing what broke when payback moves

When payback changes, don't stop at the headline. Triage it like an incident:

- Did CAC change? (channel mix, conversion rates, sales cycle)

- Did ARPA change? (pricing, discounting, packaging, mix)

- Did margin change? (COGS allocation, infra, support load)

- Did ramp change? (activation, trial conversion, implementation time)

- Did churn change before payback? (early-life churn spike)

The Founder's perspective

Payback is a forcing function for focus. If it worsens, you don't need 20 dashboards—you need one honest decomposition and a decision: fix acquisition efficiency, fix monetization, or fix delivery economics. Everything else is noise.

Practical implementation tips

A few rules keep payback trustworthy:

- Compute payback by cohort (acquisition month) to detect drift early.

- Segment aggressively: at least by channel and ACV band.

- Use consistent CAC windows: include the same cost categories each month.

- Decide how you treat onboarding labor: either include it in CAC (if it's truly acquisition) or in COGS (if it's delivery). Just don't ignore it.

- Sanity-check with retention: payback that exceeds typical customer lifetime is a red flag (see Customer Lifetime).

If you're using GrowPanel for analysis, features like cohorts, filters, ARPA, and MRR movements can help you segment payback inputs cleanly and spot whether changes are coming from pricing/mix vs retention dynamics.

Summary

Customer payback period tells you how long it takes to recover what you spent to acquire a customer, using gross profit. It matters because it links growth to cash timing: long payback increases financing risk, while short payback enables safer reinvestment.

Calculate it with gross profit (not revenue), validate it by cohort, and interpret changes by decomposing CAC, ARPA, margin, and ramp. When payback improves, scale carefully—only after confirming retention and segment behavior didn't quietly worsen.

Frequently asked questions

For many SaaS businesses, under 12 months is strong, 12–18 months is workable, and over 18–24 months is a warning sign. Enterprise can tolerate longer payback if retention is very strong and contracts are annual or multi-year. Judge it against cash runway and growth goals.

Use gross profit. Revenue payback ignores COGS and makes low-margin models look healthier than they are. Gross profit payback reflects what actually funds your business after delivery costs. If implementation or support is heavy early on, include those costs in COGS or adjust the payback calculation.

Annual prepay improves cash payback immediately, but it does not change economic payback unless price or margin changes. Founders often confuse cash collection timing with unit economics. Track both: cash payback for runway planning, and gross profit payback for whether acquisition is truly profitable.

Not automatically. Confirm the improvement is durable and cohort-based, not a one-month artifact from seasonality, discounts, or channel mix. Also check capacity constraints in sales and onboarding. Scaling spend when payback improves is rational only if conversion rates and retention remain stable at higher volume.

Classic payback assumes the customer stays long enough to repay CAC. If early churn is high, your modeled payback may be unattainable in practice. Expansion helps indirectly by increasing monthly gross profit, shortening payback. Always validate payback against retention cohorts, not just averages.