Table of contents

Enterprise value (EV)

Founders usually hear a single number—"you're worth $X"—and then make big decisions off it: dilution, venture debt, hiring pace, even whether to sell. Enterprise value (EV) is the metric that tells you what that number really means once you account for cash and debt.

Enterprise value (EV) is the value of a company's operating business, independent of how it's financed. In plain terms: EV answers, "What would it cost to buy the business itself, not its bank balance?"

What EV actually measures

EV is best thought of as a purchase price for the operating engine. It's designed to make companies comparable even when their balance sheets differ.

- Equity value (often called market cap for public companies) is what shareholders own.

- Enterprise value adjusts equity value for how much cash the company has and how much debt it owes.

Why this matters in SaaS: two companies can both be "worth $500M" on a post-money basis, but if one has $150M in cash from a recent raise and the other has $80M in venture debt, the economic value of the underlying business is not the same.

The Founder's perspective

If you're deciding between "raise vs sell" or "raise equity vs take venture debt," EV helps you separate operating value from financing. It keeps you from mistaking a bigger cash balance (or higher leverage) for a better business.

How EV is calculated

The common formula starts with equity value and adjusts for claims that are senior (debt) or non-operating (excess cash).

In venture-backed SaaS, you'll often simplify to:

- Equity value: what your last round implies (or what the acquirer offers for equity)

- Debt: venture debt, bank debt, convertible notes (deal-specific), capital leases

- Cash: cash on hand (sometimes "excess cash" depending on the deal)

A helpful shortcut is "net debt":

Then:

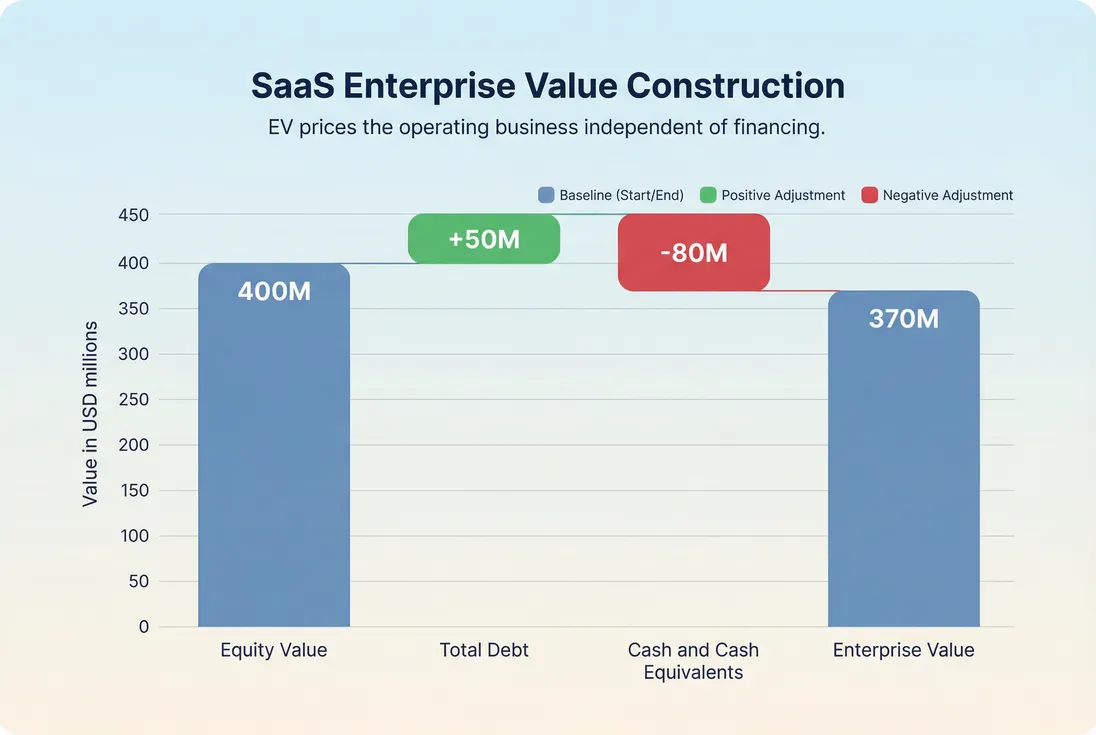

A concrete example

Assume your SaaS has:

- Implied equity value: $400M

- Venture debt: $50M

- Cash: $80M

Net debt = $50M − $80M = –$30M (you have net cash).

EV = $400M + (–$30M) = $370M.

So the market is effectively valuing the operating business at $370M, even though the equity headline is $400M.

This bridge shows why EV can be lower than the headline valuation when you hold significant cash (and higher when you carry debt).

What moves EV in SaaS

In practice, EV moves for two broad reasons:

- The market's view of your future cash flows changes (the business got better or riskier).

- Your capital structure changes (more cash, more debt, different senior claims).

Founders should learn to separate these, because they imply very different actions.

Business fundamentals (the part you can earn)

For SaaS, EV is highly sensitive to the same operating inputs investors track every week:

- Growth (usually anchored on ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) growth)

- Retention (especially NRR (Net Revenue Retention) and expansion durability)

- Gross margin (higher margin typically supports higher EV because future cash flows scale better)

- Sales efficiency (signals whether growth is "buyable" without destroying returns)

- Path to free cash flow (see Free Cash Flow (FCF))

- Risk and cost of capital (see WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital))

These drivers often show up as a multiple on revenue or ARR. For example:

That multiple expands when investors believe your future cash flows are larger and safer; it compresses when growth slows, retention weakens, or the market demands higher returns.

If you want a practical operating proxy for "are we creating value efficiently?", pair EV thinking with capital efficiency metrics like Burn Multiple and Rule of 40. EV is the destination; burn multiple is how expensive the trip is.

The Founder's perspective

If your EV multiple is compressing, don't immediately blame "the market." First check whether the inputs that justify a strong multiple are slipping: net retention, win rates, payback periods, gross margin, and your ability to sustain growth without runaway burn.

Capital structure (the part you can finance)

EV changes mechanically when you change:

- Cash balance: raising equity increases cash, which tends to reduce EV relative to equity value (all else equal), because EV subtracts cash.

- Debt: taking on debt tends to increase EV mechanically (EV adds debt), even if the operating business didn't change.

This is why EV is a better comparison tool than equity value when you're looking across companies with different funding histories.

How investors and acquirers use EV

EV is not just a public markets concept. It shows up in both fundraising narratives and M&A negotiations—often implicitly.

EV in fundraising comps

When someone says, "Similar SaaS companies trade at 8x ARR," they usually mean EV/ARR, not equity value/ARR. That's because EV strips out differences in cash and leverage, making the comp cleaner.

A practical way to use this as a founder:

- Anchor on your current ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue).

- Pick a defensible multiple range based on companies that actually resemble you (growth, NRR, margin profile, go-to-market motion).

- Convert implied EV to implied equity value using net debt.

This step is where founders often get surprised: the same EV can imply very different equity values depending on the balance sheet.

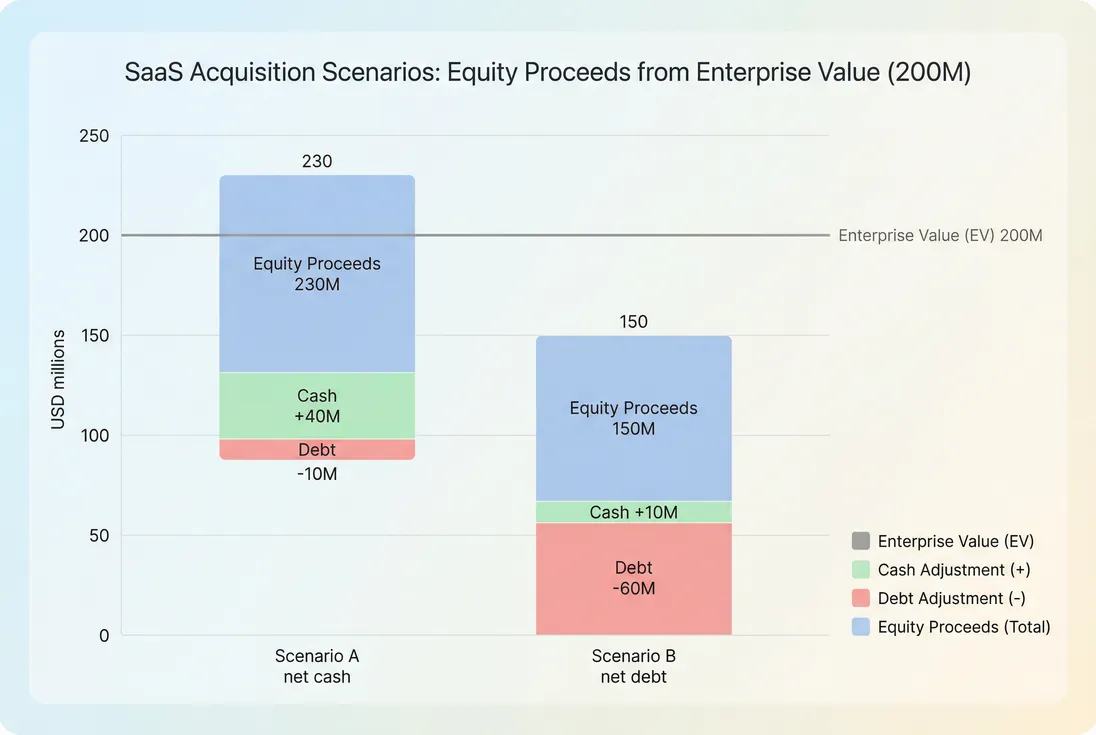

EV in M&A and what you take home

In an acquisition, "purchase price" is usually discussed as enterprise value because the buyer is buying the business operations. What you (and your shareholders) receive is closer to equity value after settling debt and considering cash.

A simplified proceeds view:

- Start with EV (price for operations)

- Subtract debt-like items the buyer won't assume for free

- Add cash that stays with the company at close (deal-specific)

- Apply other adjustments (often working capital; sometimes treatment of deferred revenue)

This is one reason founders preparing for a sale invest early in M&A Readiness: the diligence details that look "finance-y" can move real dollars at close.

The same EV can produce very different founder outcomes depending on cash and debt at close.

How founders should interpret EV changes

EV is easy to misunderstand because it can change even when your product and customers didn't.

Use this quick diagnostic:

If EV changes but ARR metrics didn't

Look for balance sheet or market-structure explanations:

- You raised cash (EV may not move much; equity value may jump).

- You took on debt (EV may rise mechanically).

- Comparable multiples changed (macro, sector sentiment, interest rates).

This is why you should track EV discussions alongside your core operating metrics like ARR growth, NRR (Net Revenue Retention), and gross margin. EV is the scoreboard; operating metrics are the reasons.

If EV changes because the multiple changed

That's the market repricing your future cash flows. In SaaS, multiples commonly compress when:

- Growth decelerates without a clear efficiency offset

- Retention weakens (especially expansion-driven NRR)

- Gross margin deteriorates (infrastructure, support, services creep)

- CAC payback stretches and growth becomes less "purchasable"

- The business becomes riskier (concentration, churn volatility)

It's often useful to translate "multiple compression" into operating workstreams:

- Retention program and expansion motion

- Pricing and packaging (see Discounts in SaaS for how discounting can quietly drag value)

- Efficiency and burn control (see Burn Rate and Burn Multiple)

- De-risking customer concentration (see Customer Concentration Risk)

The Founder's perspective

Don't try to manage EV directly. Manage the inputs the market uses to justify EV: durable growth, retention, margin, and a believable path to cash flow. The "valuation story" becomes much easier when the operating story is already true in the numbers.

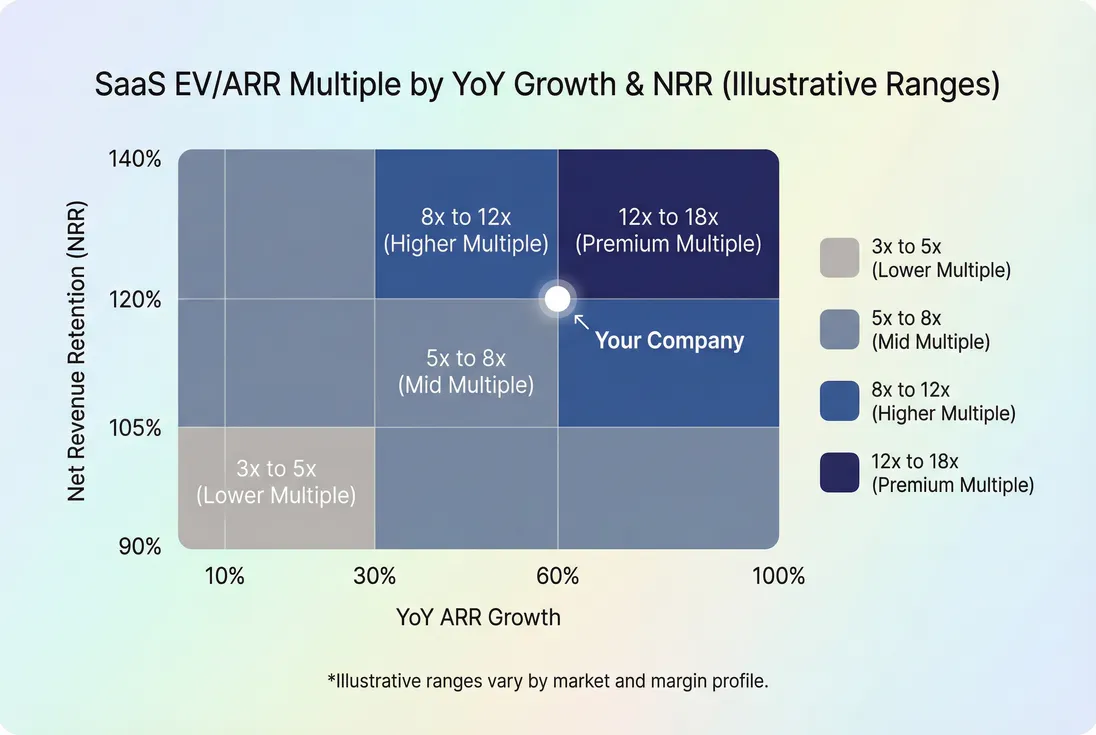

Using EV multiples without fooling yourself

Most founders encounter EV through multiples like EV/ARR. Multiples are useful—but only if you respect what they hide.

A practical EV multiple map

Instead of memorizing "good multiples," use a directional framework: higher growth + higher retention generally supports a higher EV/ARR multiple; weaker retention or slowing growth pulls it down.

Multiples usually follow fundamentals: growth and net retention are two of the biggest levers, even before you factor in margin and cash flow.

Benchmarks you can use responsibly

Below is an orientation table, not a promise. Multiples vary widely by market cycle, margins, and category leadership.

| SaaS profile (simplified) | Typical EV/ARR posture | What investors usually want to see |

|---|---|---|

| Slower growth, stable base | Lower single digits to mid single digits | Strong gross margin, low churn, clear profitability path |

| Mid growth, improving efficiency | Mid single digits to high single digits | Payback discipline, rising NRR, credible operating leverage |

| High growth, strong expansion | High single digits to teens | Durable NRR (Net Revenue Retention), category momentum, scalability |

| Best-in-class | Premium | Clear market leadership plus high margins and strong retention |

Use this table as a forcing function: "Which proof points do we have today that justify a higher band?"

Common EV traps for SaaS founders

Trap 1: Confusing cash with value creation

After a big raise, founders sometimes feel "more valuable." You may be less risky and better funded, but EV intentionally subtracts cash so you don't confuse a financing event with operating performance.

Trap 2: Treating debt as free valuation

Yes, debt mechanically increases EV. But it also increases fixed obligations and can increase risk—especially if your retention is volatile or your burn is high. Pair any leverage decision with realistic downside planning and metrics like Runway.

Trap 3: Ignoring dilution when talking EV

EV can go up while your personal outcome goes down if dilution increases faster than value creation. Keep your cap table and Dilution in SaaS implications in view whenever valuation rises are driven by financing structure, not fundamentals.

Trap 4: Using ARR without quality context

EV/ARR is only as meaningful as the ARR itself. If ARR includes heavy discounting, short-term contracts, or high churn cohorts, the multiple you "deserve" will be lower. That's why retention and cohort work matter (see Cohort Analysis).

A simple EV workflow for founder decisions

When EV comes up (fundraise, secondary, acquisition outreach), run this sequence:

Separate equity value vs EV

Ask: is the number being quoted an equity number (post-money) or an enterprise number?Compute net debt and reconcile

Use the net debt shortcut to translate between EV and equity value. This is also where hidden debt-like items can surface (deal-dependent).Tie the implied multiple to operating facts

Compare the implied EV/ARR to your growth, NRR (Net Revenue Retention), and gross margin trajectory. If it's high, identify which metrics truly justify it. If it's low, identify what would need to change.Decide what you'll optimize next quarter

EV is downstream. Your near-term levers are usually retention, pricing, sales efficiency, and margin.

The Founder's perspective

The most useful question is not "what is our EV?" It's "what would have to be true operationally for a higher EV to be rational?" That framing turns valuation anxiety into a concrete execution plan.

Quick recap

- EV is the value of the operating business, independent of financing.

- EV = equity value + debt − cash (plus other claims in some cases).

- In SaaS, EV is heavily influenced by ARR growth, retention, margins, and efficiency—and by the market's cost of capital.

- Use EV to compare across balance sheets, translate multiples into implied equity value, and avoid confusing cash or leverage with true business value.

If you want to connect EV thinking to the metrics you can manage weekly, start with ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue), NRR (Net Revenue Retention), and Burn Multiple.

Frequently asked questions

A term sheet usually talks about equity value, like pre money and post money. Enterprise value adjusts that headline number for your balance sheet. Conceptually, EV equals equity value plus debt minus cash. Two companies with the same post money can have very different EV if one is cash rich or debt heavy.

There is no universal good multiple because it moves with growth, retention, gross margin, and market risk appetite. As a rough orientation, slower growth SaaS can trade in low single digit to mid single digit EV to ARR, while high growth, high NRR businesses can justify high single digits to teens. Use comps, not averages.

When you raise equity, your equity value can increase, but your cash balance also increases. Since EV subtracts cash, EV may move less than the headline post money suggests. This is normal. It is a reminder that EV is trying to price the operating business, not the size of your bank account.

Mechanically, yes: EV adds debt. But in real markets, taking on debt can also change perceived risk and future cash flows, which can push equity value down or up. Founders should treat EV as a lens for comparing operating value across capital structures, not as a score to optimize by adding leverage.

EV is the price for the operations. Your equity proceeds are roughly EV minus debt plus cash, with additional deal specific adjustments like working capital and transaction costs. If you are cash rich, equity proceeds can be meaningfully higher than EV. If you have debt, proceeds can be much lower.