Table of contents

SaaS magic number

Founders like the SaaS Magic Number because it answers a brutally practical question: is our sales and marketing spend turning into recurring revenue fast enough to justify scaling? When the number is strong, you can hire and spend with confidence. When it's weak, "growth" can quietly become an expensive treadmill.

Definition (plain English): the SaaS Magic Number estimates how much annualized recurring revenue you generate for each dollar of sales and marketing (S&M) spend, usually with a one-quarter lag.

What the magic number reveals

At its best, the Magic Number is a speedometer for go-to-market efficiency. It compresses a lot of moving parts into one signal:

- Demand efficiency: Are you creating pipeline that converts?

- Monetization quality: Are you closing at healthy ASP (Average Selling Price) and ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) levels, without excessive Discounts in SaaS?

- Retention drag: Are churn and downgrades eating the revenue you just bought? (See MRR Churn Rate and Net MRR Churn Rate.)

The reason founders use it is decision-driven: it helps determine whether to increase S&M investment, keep it flat, or pause and fix fundamentals.

The Founder's perspective

If I add two AEs and a demand gen manager next quarter, will that likely create durable ARR growth, or just increase burn? The Magic Number is a quick check before committing to headcount and fixed costs.

How it is calculated

There are multiple "industry standard" variants. The most common looks like this:

Step 1: compute net new ARR

Net new ARR is your quarterly change in recurring run-rate, inclusive of retention effects:

If you track revenue in monthly terms, you can use MRR instead (just keep the units consistent):

Step 2: define S&M expense consistently

Most teams include:

- Sales salaries, commissions, bonuses, contractor costs

- Marketing payroll and paid acquisition

- Sales development costs

- Tools and software for sales and marketing

- Event spend and sponsorships

Common pitfalls:

- Treating one-time implementation fees as recurring (don't; see One Time Payments)

- Mixing cash collections with run-rate revenue (especially with annual upfront; see Deferred Revenue and Recognized Revenue)

- Including broad G&A that doesn't drive pipeline (keep the definition stable quarter to quarter)

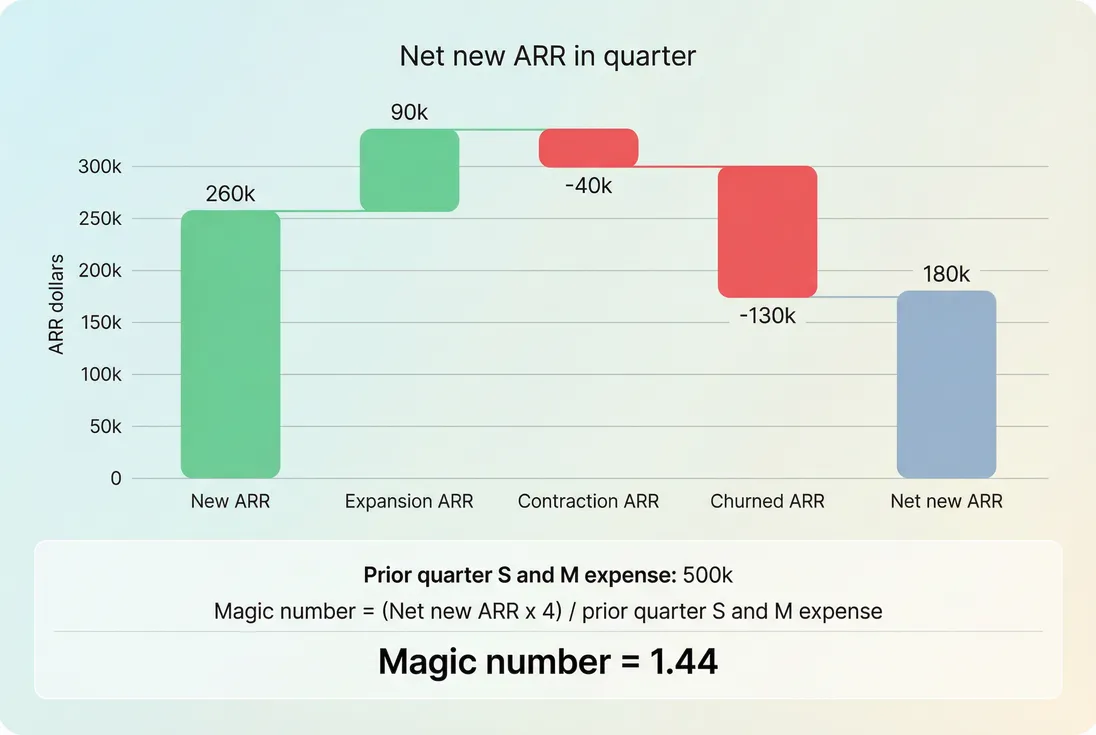

A concrete example

- Prior quarter S&M expense: $500,000

- Current quarter net new ARR: $180,000

Magic Number = (180,000 × 4) / 500,000 = 1.44

Interpretation: at the current pace, each dollar of S&M is producing about $1.44 of annualized recurring revenue. That's typically strong enough to justify continued investment, assuming retention and gross margin are healthy (see Gross Margin).

Benchmarks founders actually use

Benchmarks vary by stage and motion, but these ranges are commonly useful for decision-making:

| Magic number | What it usually means | Typical action |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.5 | Growth spend is not converting into durable ARR | Pause scaling, fix funnel and retention |

| 0.5 to 0.75 | Weak to mediocre efficiency | Tighten targeting, improve win rate and onboarding |

| 0.75 to 1.25 | Healthy | Scale cautiously; invest where you can repeat results |

| 1.25 to 1.75 | Strong | Lean in; expand channel and headcount thoughtfully |

| > 1.75 | Extremely strong or temporarily distorted | Check if you are under-spending or benefiting from one-off factors |

Two important caveats:

- Sales cycle length changes interpretation. If your Sales Cycle Length is 90 to 180 days, this quarter's spend may not show up in ARR until next quarter or later.

- Retention can inflate or crush it. High NRR (Net Revenue Retention) can make the Magic Number look great even if new logo acquisition is mediocre. Low retention can destroy it even when top-of-funnel is fine.

The Founder's perspective

I use the Magic Number as a "permission slip" to scale. If it's below 0.75 for two quarters, I assume we have a go-to-market problem to fix before hiring more quota capacity.

What moves it up or down

The Magic Number is a ratio, so founders should think in two levers: the numerator (net new recurring revenue) and the denominator (S&M spend).

Numerator drivers: net new ARR

New customer ARR

- Better ICP and positioning increases win rate (see Win Rate)

- Higher pricing and packaging improves revenue per deal

- Lower discounting improves the same

Expansion ARR

- Seat growth, usage growth, add-ons

- Better onboarding and time-to-value (see Time to Value (TTV))

Churn and contraction

- Weak product value, poor support, failed onboarding

- Billing issues and failed payments (see Involuntary Churn)

- Bad-fit customers from overly broad targeting

A useful discipline: compute a "new business only" version alongside the standard metric by using only New ARR in the numerator. If the standard Magic Number is high but the new-business version is low, your growth is being carried by expansion, not acquisition.

Denominator drivers: sales and marketing spend

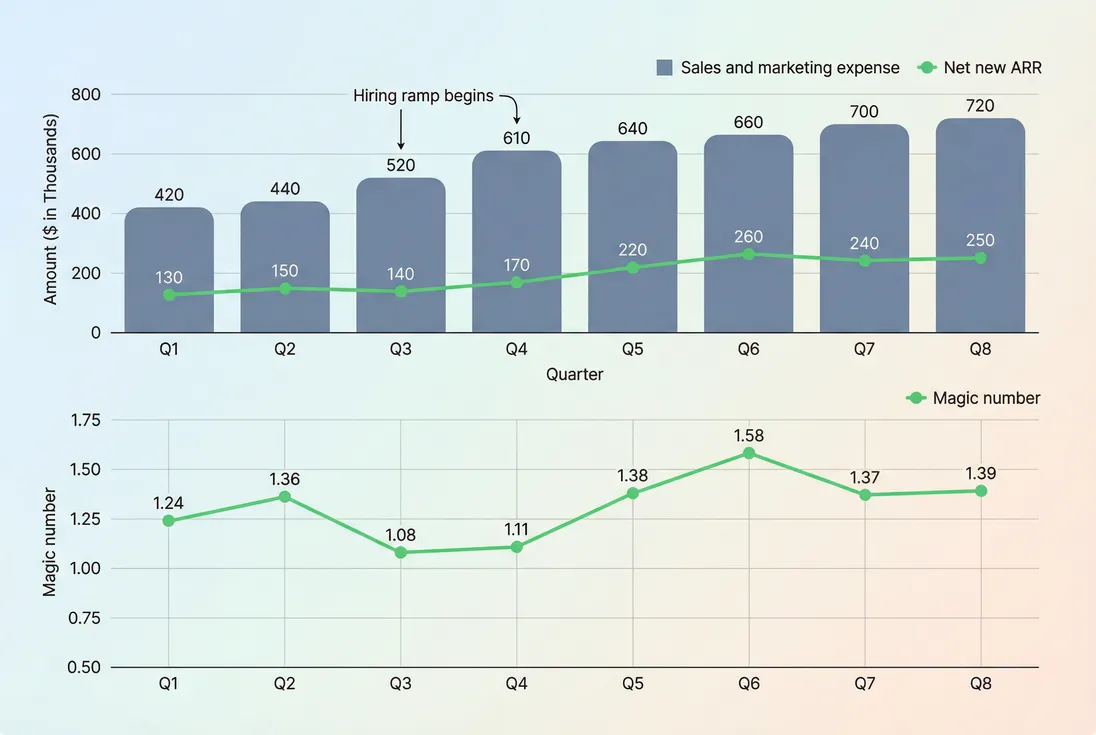

Headcount ramps

- New reps reduce efficiency temporarily (ramp time + low capacity utilization)

- This is why looking at a single quarter can be misleading

Channel mix

- Paid channels can scale fast but deteriorate if you saturate the audience

- Outbound can be efficient but often ramps slowly

Operating discipline

- Tool sprawl, agency spend, and low-quality lead volume can inflate S&M without improving ARR

How founders use it to make decisions

The Magic Number is most valuable when it is paired with a few "companion metrics" that explain why it is high or low.

Use it for spend scaling

A practical operating rule:

- If Magic Number is consistently above 1.0, you can justify increasing S&M investment, as long as retention is stable.

- If it's consistently below 0.75, scaling spend is likely to increase burn faster than ARR.

Tie this into capital efficiency thinking with Burn Multiple and Capital Efficiency. Magic Number tells you about S&M efficiency; Burn Multiple reflects the whole company's efficiency.

Use it for diagnosing the bottleneck

When the Magic Number drops, isolate the cause with a quick decomposition:

- Did net new ARR fall because:

- new ARR slowed (pipeline, win rate, cycle length)?

- expansion slowed (product adoption)?

- churn rose (retention problem)?

- Or did it fall because S&M spend rose (hiring, paid ramp) before results landed?

This is where a bridge view of recurring revenue helps. If you track MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and movements like new, expansion, contraction, and churn, you can see which component changed first.

If you're using GrowPanel, the MRR movements view and filters can help you isolate whether the issue is driven by a segment (self-serve vs sales-assisted, SMB vs mid-market, a region, or a plan tier). See MRR movements and Filters.

Use it for planning hiring pace

A common mistake is hiring ahead of evidence. Use the Magic Number trend (not one quarter) to set hiring pace:

- Rising trend: add capacity; keep an eye on rep ramp and quality.

- Flat trend: hire selectively; focus on conversion improvements.

- Falling trend: pause hiring; fix the biggest conversion or retention leak.

The Founder's perspective

I don't want to "feel" like we can scale. I want proof. A stable or improving Magic Number over two to three quarters is one of the clearest proofs that adding S&M spend won't just increase burn.

When it breaks (and how to adjust)

The Magic Number is simple, which is why it's popular. That simplicity also creates failure modes.

Long enterprise sales cycles

If your cycle is 6 to 12 months, prior-quarter spend may not map to current-quarter ARR changes. Two fixes:

- Use a two-quarter lag in the denominator.

- Use trailing averages (see T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average)) to reduce noise.

Big annual contract timing

One large deal can dominate net new ARR in a quarter, making the Magic Number spike. Countermeasures:

- Track the metric quarterly, but interpret it on a rolling 4-quarter view.

- Split by segment to see if SMB motion and enterprise motion are behaving differently.

Expansion-heavy businesses

If Expansion MRR is the dominant growth driver, the standard metric can encourage overconfidence in acquisition. Add two companion calculations:

- New-only Magic Number: uses only New ARR.

- Expansion contribution: percentage of net new ARR from expansion.

This prevents you from scaling acquisition when your real engine is account growth.

Pricing changes and discount policy shifts

A price increase can improve Magic Number quickly, but it can also raise churn later if value perception lags. Watch:

- Logo Churn for early warning

- GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) and NRR (Net Revenue Retention) for impact on existing customers

Early-stage volatility

At low ARR, the metric is noisy. Two deals can swing the ratio dramatically. In that stage:

- use it as a trend, not a target

- pair it with CAC Payback Period and LTV:CAC Ratio to avoid optimizing a single number

Interpreting changes without overreacting

A founder-relevant way to interpret movement is to ask what changed first: spend or revenue.

If the magic number falls

Most common causes:

- Hiring ramp: spend rose but bookings haven't landed yet.

- Pipeline quality drop: lead volume grew but conversion and win rate fell.

- Retention shock: churn or contraction spiked due to product issues or poor-fit customers.

What to do next (sequenced):

- Confirm it's not timing: check sales cycle and ramp effects.

- Break net new ARR into new vs expansion vs churn.

- Make one focused change (ICP, onboarding, pricing, channel), then watch for two quarters.

If the magic number rises

This can be great—or suspicious.

Healthy reasons:

- higher ASP, better packaging

- improved conversion or win rate

- churn reduction

Potentially misleading reasons:

- one large deal

- paused spend (denominator shrank)

- expansion surge masking weak new business

The best practice is to treat the Magic Number as a prompt to investigate, not a standalone "grade."

A simple operating cadence

If you want this metric to drive better decisions (not just board-deck theater), use a consistent cadence:

- Quarterly calculation with a documented definition of net new ARR and S&M expense.

- Bridge the numerator into new, expansion, contraction, churn.

- Segment it by motion (self-serve vs sales-led), plan, or ICP tier.

- Review alongside:

That combination tells you not only "is it efficient?" but also "is it durable?" and "can we scale it?"

Quick takeaway

The SaaS Magic Number is a practical growth-efficiency metric: net new recurring revenue generated per dollar of prior-quarter S&M spend. Use it to decide when to scale go-to-market investment, but don't trust it blindly—break it into components, adjust for sales cycle lag, and validate it against retention and payback.

Frequently asked questions

As a rule of thumb, below 0.5 signals inefficient growth, 0.5 to 0.75 is mediocre, 0.75 to 1.25 is healthy, and above 1.25 is excellent. Context matters: long sales cycles, heavy onboarding, and enterprise contracts can temporarily depress the number even when fundamentals are fine.

Use the version that matches how you manage the business and keep it consistent. ARR is common for sales-led motions and annual contracts; MRR can be more intuitive for monthly plans. The key is to measure recurring run-rate change, not cash collected, and to align the timing with spend.

Because spend typically shows up in revenue with a lag. Pipeline created in one quarter often closes in the next. Using prior quarter spend helps the metric reflect the return on the spend that actually drove the growth. If your sales cycle is longer, consider a two-quarter lag.

Yes. A high number can come from expansion and price increases rather than efficient new customer acquisition, or from temporarily low spend because you paused hiring. Always break the numerator into new, expansion, churn, and contraction to see what is really driving performance and what is sustainable.

First check for timing effects: hiring ramps, seasonality, and sales cycle delays can cause a short-term dip. Then diagnose whether the issue is demand (pipeline, win rate), monetization (pricing, discounting), or retention (churn, contraction). Make one targeted change and track it for two quarters.