Table of contents

Runway

Runway is the difference between running the company and running out of time. If you misread it, you'll hire too early, raise too late, or negotiate from weakness.

Runway is the number of months your company can keep operating before cash reaches zero (or a minimum safety balance), based on your current net burn. It's a cash survival metric, not a growth metric—and it should directly shape hiring plans, spend levels, and fundraising timing.

What runway reveals

Runway answers one brutally practical question: how long can you keep making payroll without new capital or a major change in cash flow?

What it's great for:

- Fundraising timing. Knowing when you must start a process versus when you can wait for stronger traction.

- Hiring pacing. Deciding whether a "key hire" is affordable now or should be delayed until cash flow improves.

- Spending confidence. Greenlighting experiments (paid acquisition, new market) only if you can survive the downside.

- Negotiating leverage. The more runway you have, the less you "need" a deal.

What runway is not:

- A measure of product-market fit. Use Retention, NRR (Net Revenue Retention), and GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) for that.

- A proxy for revenue. Use MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue).

- A profitability metric. Use Free Cash Flow (FCF) or operating metrics like Operating Margin.

The Founder's perspective: Runway is your decision clock. When runway is long, you can optimize for learning and long-term value. When runway is short, you're optimizing for survival—often at the expense of product quality, retention, and culture.

How runway is calculated

The simplest version is cash divided by net burn.

Where:

- Cash available usually means cash in bank (sometimes plus very liquid equivalents), often minus a minimum safety buffer you refuse to go below.

- Net burn per month is the monthly decrease in cash from operations.

A practical net burn definition:

Use a trailing average, not one month

One month can be distorted by annual invoices, bonus payouts, tax payments, or a one-time vendor bill. Most founders should compute runway using a trailing 3-month average burn:

- Pull the last 3 months of actual cash movement.

- Average net burn across those months.

- Recompute runway monthly (or weekly if you're under 9 months).

If your cash flows are lumpy (annual prepay, usage spikes, refunds), using T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average) logic makes runway far more stable and decision-useful.

Decide what "cash available" means

Founders often inflate runway by including cash they can't really use.

Common adjustments:

- Minimum cash buffer. Example: keep at least one payroll cycle + taxes untouched.

- Restricted cash. Exclude anything legally restricted.

- Debt facilities. Only include undrawn debt if it is truly available (no covenant issues, no near-term expiration). Even then, track "cash runway" and "cash plus credit runway" separately.

Quick example

- Cash in bank: $1.8M

- Safety buffer: $300k

- Net burn (3-month average): $150k per month

Cash available = $1.5M → runway = 10 months.

This is the moment where founder behavior should change: 10 months means you likely need to start a fundraising plan now, or have a very credible near-term path to reducing burn.

What moves runway in real life

Runway changes for only two reasons:

- Your cash available changes.

- Your net burn changes.

Everything else is a driver of those two.

1) Hiring and fixed costs

Hiring is the most common runway killer because it increases burn in a way that's hard to reverse quickly. A few hires can permanently step up monthly payroll, benefits, tooling, and management overhead.

What to watch:

- "Runway impact per hire" (roughly: fully loaded cost divided by current burn).

- Whether hiring increases growth efficiency (tie to Burn Multiple for context).

2) Revenue collection timing (not just revenue)

Runway is cash. Cash depends on when customers pay.

Two SaaS businesses can have identical MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and radically different runway if:

- One collects annually upfront.

- One bills monthly and has slow collections.

- One has meaningful refunds, chargebacks, or payment failures (see Refunds in SaaS and Chargebacks in SaaS).

If you invoice (especially in B2B), runway should be paired with Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging. A growing AR balance can make runway look stable while cash silently tightens.

3) Gross margin and COGS creep

If hosting, data, support, or third-party fees rise faster than revenue, you're effectively increasing burn even if headcount stays flat. Track COGS (Cost of Goods Sold) and Gross Margin.

A common failure mode: usage costs scale up before pricing does (especially with AI, data, or heavy infrastructure).

4) Retention and expansion dynamics

Runway is extremely sensitive to retention because retention changes future collections without adding acquisition spend.

Drivers to connect:

- If Logo Churn rises, future cash receipts shrink.

- If Net MRR Churn Rate improves (more expansion, less contraction), runway can stabilize even without cost cuts.

- If you sell annual contracts, renewal seasonality can create "fake runway" during booking months and a cliff later.

Use Cohort Analysis to understand whether recent cohorts behave worse (runway risk rises) or better (runway risk falls).

5) One-time cash events

Examples:

- Annual vendor renewals

- Tax payments

- Litigation, security incident response

- Hardware buys

- Debt repayment

These can cut runway quickly, so founders should track a "base burn" and a "fully loaded burn" that includes expected one-offs.

When runway breaks as a metric

Runway is powerful, but it can mislead you in predictable scenarios.

Lumpy annual prepay

Annual upfront payments increase cash now, extending runway—but the business may still be structurally unprofitable. You've pulled cash forward. If renewals are weak, you'll face a later cliff.

Pair runway with:

- GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) to pressure-test renewal risk

- Natural Rate of Growth to understand what growth looks like without heroic spend

Fast growth with delayed costs

Some growth investments have delayed cost impact:

- Support headcount needed only after onboarding volume grows

- Infrastructure scaling after usage rises

- Compliance costs after enterprise deals land

A runway chart that looks stable can suddenly worsen as those costs arrive. When your growth rate changes, revisit your burn forecast—not just your burn history.

"Runway theater" through underinvestment

You can extend runway by pausing sales and product investment—but that may increase churn, slow growth, and reduce your ability to raise later. The goal isn't maximum runway. The goal is enough runway to reach the next value inflection.

The Founder's perspective: Don't optimize runway in isolation. Optimize runway relative to the milestone that makes capital cheaper: repeatable acquisition, retention stability, enterprise reference customers, or a clear path to breakeven.

How much runway is enough

There's no universal benchmark, but founders need a policy.

A pragmatic way to set targets is by stage and go-to-market motion (sales cycles and funding timelines differ materially between PLG and enterprise sales).

| Situation | Minimum runway | Healthier runway | Why |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-seed / searching for GTM | 12 months | 18–24 months | Experiments take time; resets are common |

| Seed / proving repeatability | 12 months | 15–21 months | Need room for iteration and hiring mistakes |

| Series A / scaling | 15 months | 18–24 months | Scaling costs arrive before efficiency improves |

| Enterprise sales cycles (6–12 months) | 15 months | 21–27 months | Pipeline conversion is slower and lumpier |

| Near breakeven, stable retention | 9 months | 12–18 months | Lower financing risk if unit economics are proven |

Two founder rules that hold up well:

- If runway is under 12 months, you're in a constrained operating mode. Spending decisions must be reversible.

- If runway is under 9 months, you should already be acting. Either you're fundraising, cutting burn, or both.

Link runway to efficiency by keeping an eye on Burn rate and Burn Multiple. Long runway with terrible efficiency can still fail; short runway with excellent efficiency can often raise.

How founders use runway to make decisions

1) Set a fundraising trigger, not a guess

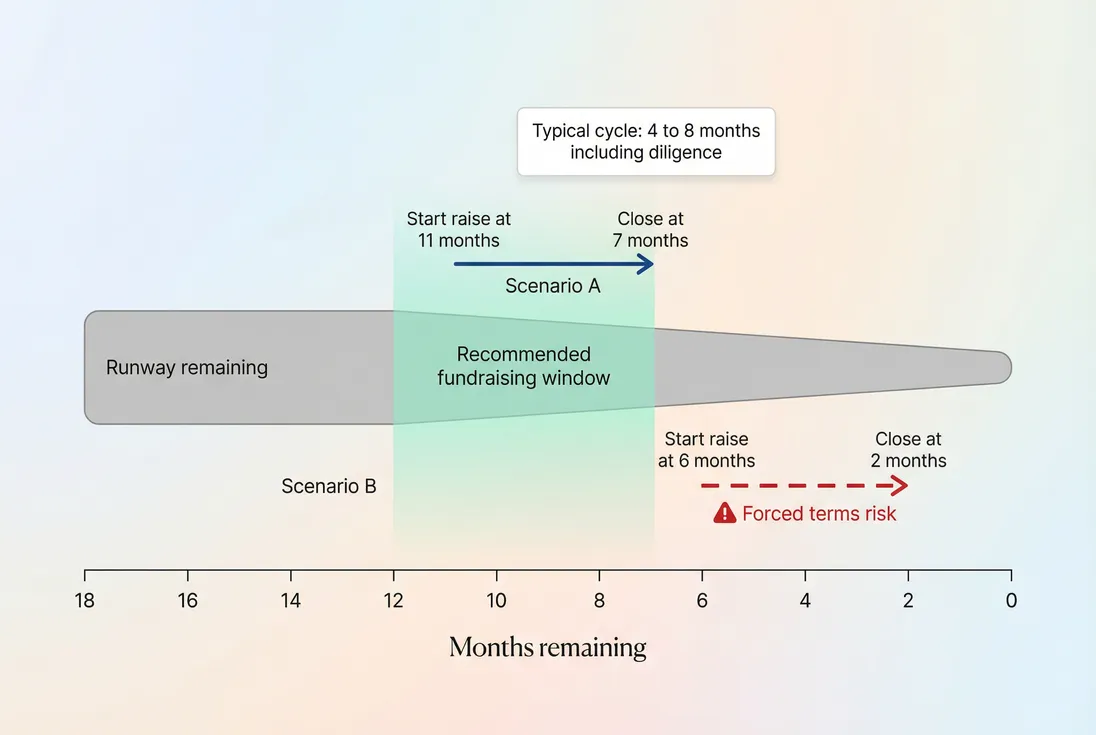

Fundraising is not instantaneous. A clean process often takes 4–8 months, and longer if metrics wobble.

A simple trigger system:

- 12 months runway: start building the narrative, metrics pack, and target list

- 9 months runway: begin meetings in earnest

- 6 months runway: you're in danger of forced terms; cut burn and raise simultaneously

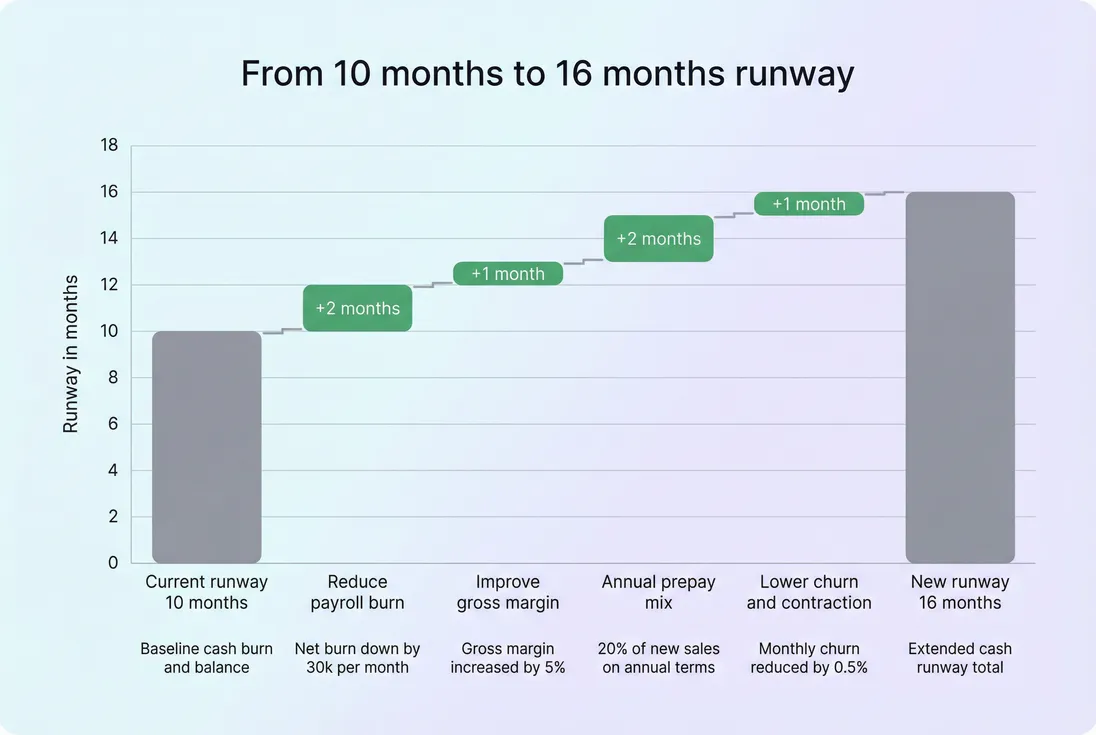

2) Choose the right "runway lever"

Founders usually reach for cost cuts first, but the best lever depends on what's driving burn.

Use this mental model: extend runway by improving net burn, increasing cash, or both.

Common levers and their tradeoffs:

- Reduce spend (fastest): hiring freeze, renegotiate tools, cut paid acquisition with low payback

- Risk: can hurt growth and retention if you cut muscle

- Improve gross margin: optimize infrastructure, reprice usage-based components, reduce support cost-to-serve

- Risk: takes time and engineering focus

- Improve collections: annual prepay incentives, better billing ops, reduce delinquency, tighten refund policy

- Risk: can increase churn if handled poorly (see Discounts in SaaS and Billing Fees)

- Increase revenue quality: price increases, packaging, expansion motion

- Risk: needs product value clarity and churn risk management

3) Tie runway to unit economics milestones

Runway matters most relative to what you can accomplish before it runs out.

Common milestone targets:

- Payback improvement: get CAC Payback Period into a fundable range

- Retention stability: improve MRR Churn Rate and Logo Churn

- Expansion engine: demonstrate consistent Expansion MRR

- Pricing power: raise ARPA (Average Revenue Per Account) without increasing churn

If you can't credibly reach a milestone with current runway, you need to either (a) reduce burn, (b) raise sooner, or (c) change scope.

4) Make runway visible, then operationalize it

Runway shouldn't live only in a spreadsheet the CFO updates monthly. Make it part of operating rhythm:

- Review runway monthly in leadership meeting.

- Reforecast after major decisions (hire plan, pricing change, contract shift).

- Track leading indicators that will hit cash later: churn signals, pipeline quality, AR aging, infrastructure growth.

If you already monitor recurring revenue health in tools that break down MRR drivers (new, expansion, contraction, churn), your runway conversations become much more actionable because you can point to the specific revenue movements that will change future collections.

A simple runway operating checklist

Use this when runway is tightening (or when you want to avoid tightening).

- Compute runway with a trailing average burn (avoid one-month noise).

- Separate operating burn from financing (fundraising proceeds are not "income").

- Create a 90-day cash plan with the top 3 levers and owners.

- Pressure-test retention with Cohort Analysis and churn metrics.

- Set a fundraising trigger (typically 9–12 months remaining).

- Recalculate after every major decision (especially hiring and pricing).

Runway is simple math, but it's not a simple management problem. Founders who treat it as a living operational constraint—rather than a quarterly check-in—make cleaner decisions, avoid panic cuts, and raise capital from a position of strength.

Frequently asked questions

For most early-stage SaaS, 12 months is the minimum to stay out of panic mode, and 18 to 24 months is healthier if growth is still being proven. The right target depends on sales cycle length, renewal timing, and fundraising conditions. Short runway forces rushed cuts and weak negotiating leverage.

Use net burn for decision-making because it reflects how fast cash is actually shrinking after collections. Gross burn is useful for cost discipline, but it can hide improvements in cash collections or new recurring revenue. Track both: gross burn to manage spending, net burn to manage survival and fundraising timing.

Treating booked revenue as cash. Annual contracts, invoices, and recognized revenue do not pay payroll. Runway is a cash metric, so it must reflect when money hits the bank and when it leaves. If you sell annual upfront, runway may look strong temporarily and then fall sharply later.

Annual prepayments improve runway immediately because cash arrives upfront, even though revenue is recognized over time. That said, it is not free money; you still owe service delivery. Use cash runway for survival, but pair it with retention metrics like GRR and NRR to avoid mistaking prepay for real sustainability.

A practical rule is to start when you have 9 to 12 months of runway left, because fundraising often takes 4 to 8 months including diligence and legal. If your metrics are volatile or sales cycles are long, start earlier. Waiting until 4 to 6 months usually forces bad terms or emergency cuts.