Table of contents

Sales efficiency

Sales efficiency answers a question founders feel every month: are we buying real growth, or just spending more to stand still? If your sales and marketing bill goes up 30% and new ARR stays flat, you don't have a "growth" problem—you have an efficiency problem that will eventually show up as slower hiring, lower valuation, or a painful reset.

Definition (plain English): Sales efficiency measures how much new recurring revenue you generate for each dollar spent on sales and marketing, typically using a one-period lag so spending has time to convert into closed revenue.

What sales efficiency reveals

Sales efficiency is a practical "throughput" metric for your go-to-market system. It compresses a lot of moving parts—pipeline quality, win rate, sales cycle length, pricing, discounts, and churn—into one number you can use to pace hiring and budgets.

The most common SaaS version looks like this:

If you track monthly recurring revenue instead of annualized revenue, you'll usually annualize it:

How to interpret the number:

- 1.0 means: every $1 spent on sales and marketing produced $1 of new ARR (annualized), measured with a lag.

- 0.5 means: $1 produced $0.50 of new ARR (you're paying a lot for growth).

- 1.5 means: $1 produced $1.50 of new ARR (you can usually scale, assuming retention is solid).

The Founder's perspective

Sales efficiency is the metric I use to decide whether to add headcount or fix the system. If efficiency is strong, hiring is an execution problem. If it's weak, hiring is a distraction from the real issue—positioning, conversion, or retention.

How founders calculate it (without fooling themselves)

The biggest risk with sales efficiency isn't the math—it's mixing inconsistent definitions of "spend" and "new ARR," which creates false confidence or false alarms.

Step 1: Define the revenue numerator

Most teams choose one of two numerators:

1) Gross new ARR (acquisition-focused):

- New ARR + Expansion ARR

2) Net new ARR (durability-focused):

- New ARR + Expansion ARR − Churn ARR − Contraction ARR

If you're already tracking MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) and movements like expansion and churn, the net version tends to be the most decision-useful because it bakes in whether customers stick around long enough to justify spend.

A clean "net new ARR" definition is:

Related metrics that help you sanity-check the numerator:

- Net MRR Churn Rate (if net churn is high, net efficiency will disappoint)

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) (strong NRR can "rescue" efficiency)

- Expansion MRR and MRR churn rate (to isolate what changed)

Step 2: Define the spend denominator

At minimum, include fully loaded sales and marketing expenses for the period you're lagging:

- Sales payroll (base + commissions + bonuses)

- Sales tools (CRM, enrichment, dialers)

- Marketing payroll

- Paid acquisition, events, sponsorships

- Agency and contractor spend

- Sales engineering / solutions consultants (if directly supporting sales)

- A reasonable allocation of GTM leadership (VP Sales, Head of Marketing)

Common founder mistake: excluding commissions or excluding marketing because "sales closes deals." That makes the ratio look better while your bank account tells the truth.

Step 3: Use a lag that matches your sales cycle

The purpose of the lag is simple: spending happens first; revenue follows.

- Short cycle (self-serve / SMB): 0–1 month lag may be reasonable.

- Typical mid-market: 1 quarter lag is common.

- Enterprise: 2+ quarters may be necessary, or you'll systematically understate efficiency during periods of pipeline build.

Tie this to Sales Cycle Length: if the median cycle is 75 days, a one-quarter lag will be directionally right; if it's 180 days, it won't.

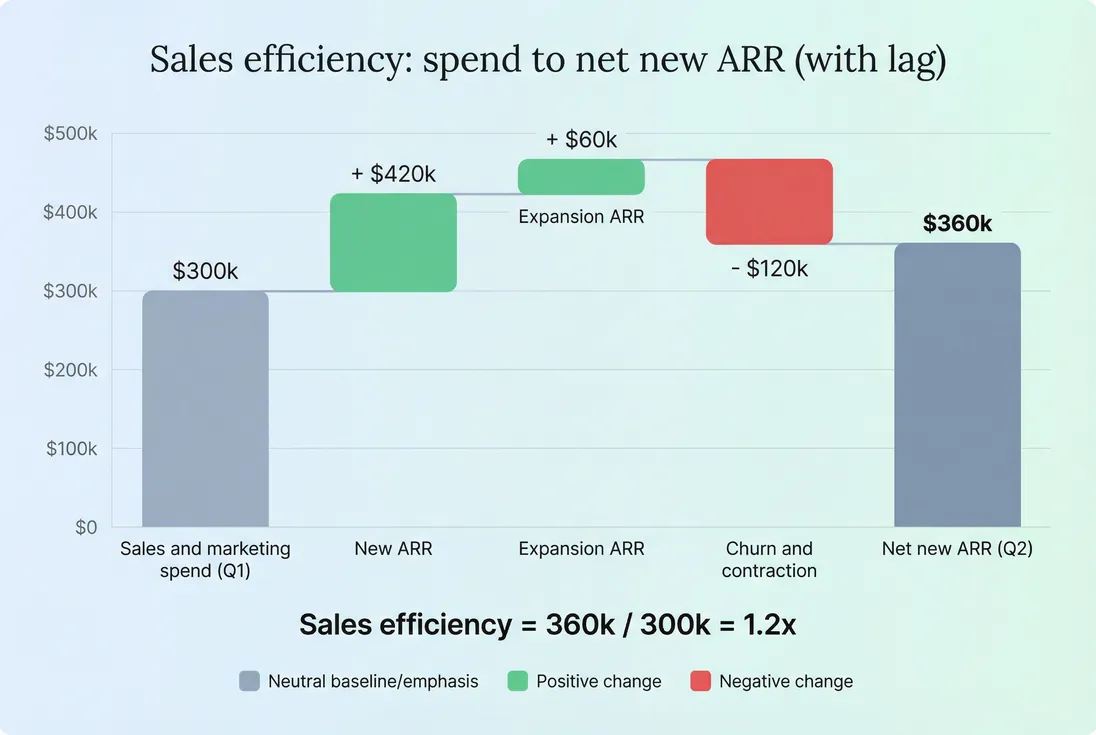

A concrete example

Assume:

- Q1 S&M spend: $300k

- Q2 results: New ARR $420k, Expansion ARR $60k, Churn+Contraction $120k

Net new ARR (Q2) = $360k

Sales efficiency = 360 / 300 = 1.2x

Now compare that to a quarter where churn worsens:

| Scenario | New ARR | Expansion ARR | Churn + Contraction | Net new ARR | Q1 Spend | Sales efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy retention | 420k | 60k | 120k | 360k | 300k | 1.2x |

| Retention slipped | 420k | 60k | 220k | 260k | 300k | 0.87x |

Nothing changed in acquisition. The metric is telling you the truth: your go-to-market spend is now paying for churn.

The Founder's perspective

If sales efficiency drops but pipeline and win rate are stable, I assume retention is the culprit until proven otherwise. It's usually faster to fix onboarding and churn drivers than to "sell harder" into a leaky bucket.

What "good" looks like in practice

There isn't one universal benchmark because the right target depends on:

- Gross margin and cash constraints (see Burn Rate and Runway)

- Growth expectations (see Rule of 40)

- Contract length and payment terms (annual prepay boosts cash but not necessarily efficiency)

- How much expansion you expect (NRR profile)

That said, founders often use these operating ranges (quarterly measurement, lagged):

| Sales efficiency (net) | Typical interpretation | Common action |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.5x | GTM is struggling or mis-measured | Freeze hiring, tighten ICP, fix funnel + onboarding |

| 0.5x to 0.75x | Mediocre efficiency | Focus on win rate, cycle time, pricing, retention |

| 0.75x to 1.25x | Healthy | Scale selectively; maintain message/channel discipline |

| > 1.25x | Strong | Consider accelerating hiring if retention stays strong |

How this relates to other "efficiency" metrics:

- Sales efficiency is closely related to the SaaS Magic Number. Many teams use the terms interchangeably; the core idea is the same: ARR created per S&M dollar, with a lag.

- Sales efficiency vs. payback: Pair it with CAC Payback Period. Efficiency can look fine while payback is long if ASP is low, margins are thin, or churn is high.

- Sales efficiency vs. capital efficiency: Pair it with Burn Multiple to see whether the whole company—not just GTM—converts spend into growth efficiently.

Why sales efficiency moves (the real drivers)

Sales efficiency changes for only a handful of underlying reasons. The trick is diagnosing which one you're dealing with before you change headcount or budgets.

Driver 1: Pipeline quality and win rate

If leads are getting worse or your ICP drifted, you'll see:

- Lower Win Rate

- More stalled deals

- More discounting pressure

- Efficiency down 1–2 quarters later

A fast diagnostic is to segment by acquisition source and deal size (even in a spreadsheet) and check whether the drop is concentrated.

Driver 2: Sales cycle length

Longer cycle → same spend → revenue pushed out → near-term efficiency drops.

This is why efficiency often falls when you:

- move upmarket

- add procurement-heavy industries

- switch from monthly to annual contracts with security review

If you're intentionally moving upmarket, don't "fix" the metric by cutting spend; fix your measurement by using an appropriate lag and by tracking cycle length separately.

Driver 3: ASP, packaging, and discounting

Your efficiency numerator is ARR. If you raise ASP (Average Selling Price) without tanking win rate, efficiency improves quickly.

Discounting does the opposite, especially if it becomes the default to hit quota. If discounting increased, go re-read Discounts in SaaS and make sure you're treating discounted MRR consistently across reporting.

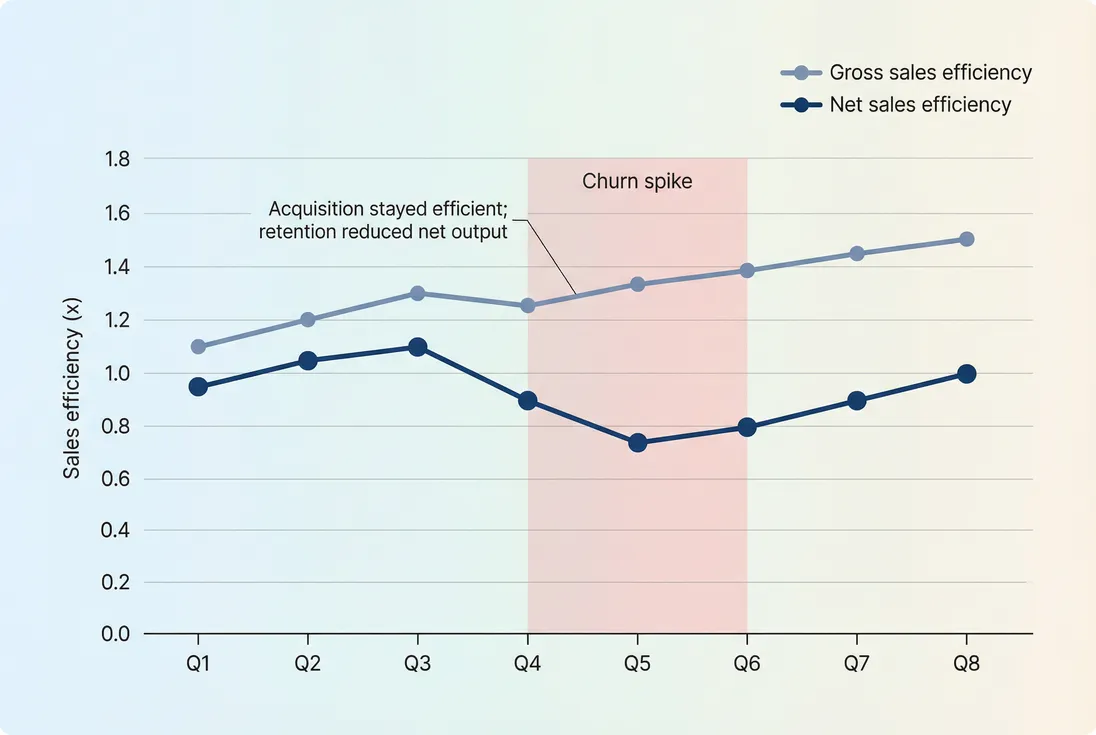

Driver 4: Retention and expansion

Retention doesn't just impact "post-sale" metrics; it directly changes net sales efficiency.

- Better onboarding and product value → higher NRR → net efficiency up

- Higher churn (or contraction) → net efficiency down, even if acquisition is fine

This is why pairing sales efficiency with GRR (Gross Revenue Retention) is powerful: GRR tells you whether the base is leaking regardless of expansion.

Driver 5: Team ramp and org design

Efficiency dips are normal when you:

- hire multiple reps at once

- add a new sales layer (SDRs, AEs, AMs)

- change territories or verticals

- roll out new tooling and process

But "normal" has a limit. If fully ramped reps are still inefficient, ramp is not the issue.

A simple operational split that helps:

- Efficiency from fully ramped reps (steady-state)

- Investment in ramp (temporary drag)

When sales efficiency breaks (and what to do)

Sales efficiency is useful because it's fast—but that speed creates traps.

Trap 1: Using bookings when your product churns fast

If you count signed ARR but churn happens within 90 days, efficiency will look great right up until reality hits. In that case, prefer net new ARR and monitor early retention with Cohort Analysis.

Trap 2: Mixing cash collected with ARR created

Annual prepay improves cash flow, but sales efficiency is not a cash metric. If you want to understand cash timing, look at Deferred Revenue and, if you have invoicing complexity, Accounts Receivable (AR) Aging.

Trap 3: One-off events and seasonality

Conferences, big launches, or a single enterprise deal can swing a quarter. Don't overreact to one period—use a trailing average (see T3MA (Trailing 3-Month Average)) or look at multi-quarter trends.

Trap 4: Counting spend in the wrong place

If Customer Success is doing heavy expansion selling, but their cost sits outside S&M, your efficiency will look artificially high. Decide whether expansion is a sales motion or CS motion, and measure consistently.

How founders use sales efficiency to make decisions

Sales efficiency becomes truly valuable when you turn it into a few default operating rules.

1) Hiring and headcount pacing

Use efficiency to decide whether to hire more GTM capacity or fix constraints first.

A practical decision pattern:

- If net efficiency is consistently > 1.0x and pipeline coverage is healthy, adding reps is often rational.

- If net efficiency is < 0.75x, hiring usually amplifies waste unless you have a clear, testable plan to improve conversion or retention.

Pair this with Sales Rep Productivity so you don't blame the market for what's actually a rep enablement issue.

The Founder's perspective

I don't greenlight a hiring plan just because we want to grow. I greenlight it when the current system proves it can turn dollars into ARR predictably. Sales efficiency is the quickest proof.

2) Budget allocation across channels

Efficiency is most actionable when segmented:

- inbound vs outbound

- paid vs organic

- partner channel vs direct

- SMB vs mid-market vs enterprise

Even a rough split helps you stop funding channels that "feel busy" but don't produce durable ARR.

If you're already tracking revenue movements, segmenting net new revenue is easier when you can consistently classify new vs expansion vs churn (see Churn Reason Analysis to connect churn drivers back to acquisition promises).

3) Pricing and packaging decisions

Sales efficiency often improves more from pricing clarity than from incremental funnel tweaks.

Signals you may have a pricing/packaging issue:

- win rate is stable but ASP is falling

- discounts are creeping up to hit quota

- sales cycle is getting longer due to value ambiguity

Revisit:

4) Retention investment (the hidden lever)

If net efficiency is low but gross efficiency is fine, the most leveraged path is often:

- faster time-to-value (see Time to Value (TTV))

- onboarding completion (see Onboarding Completion Rate)

- churn reduction (see Customer Churn Rate, Voluntary Churn, and Involuntary Churn)

Founders sometimes treat retention as a "later" problem. Sales efficiency punishes that thinking quickly—because churn effectively taxes every new dollar of ARR you create.

5) Aligning the org on one scorecard

Sales efficiency works best as part of a small set of linked metrics:

- Sales efficiency (is GTM spend converting to ARR?)

- CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) (how expensive is it to win customers?)

- CAC Payback Period (how fast do we recover it?)

- NRR (Net Revenue Retention) (does revenue stick and expand?)

- Burn Multiple (does the whole company convert spend into growth?)

If these disagree, that disagreement is the insight.

Implementation notes (so the metric stays trustworthy)

A few rules keep sales efficiency from turning into an argument every month:

- Document your definition once. Especially what counts in S&M spend.

- Be consistent about lag. Change lag only when sales cycle meaningfully changes.

- Track both gross and net. Gross diagnoses acquisition; net diagnoses the business.

- Use trailing averages for decisions. One quarter is noise; two to four quarters is signal.

- Sanity-check against retention. If NRR drops, expect net efficiency to drop soon.

If your reporting already separates new, expansion, contraction, and churn movements, you'll have the building blocks to compute net new revenue cleanly over time and to filter by segment when diagnosing changes (see filters and MRR movements).

The takeaway

Sales efficiency is the founder-friendly bridge between go-to-market activity and financial reality. It tells you whether your next dollar into sales and marketing is likely to create durable ARR—or whether you should pause, diagnose, and fix the system before you scale it.

When you use it with the right lag, consistent spend, and a net view that respects churn, it becomes a dependable operating lever: hire when it's strong, fix when it's weak, and always investigate the drivers rather than the number itself.

Frequently asked questions

It depends on stage and motion, but many founders use 0.75 to 1.25 as a healthy range when measuring quarterly net new ARR against the prior quarter's sales and marketing spend. Above 1.25 usually supports scaling. Below 0.5 suggests messaging, funnel, or retention problems.

Use gross when you want to judge pure acquisition performance (new and expansion ARR before churn). Use net when you want to know whether the go-to-market machine is truly creating durable growth after churn and contraction. If gross looks fine but net is weak, retention is your hidden constraint.

New reps depress efficiency during ramp because spend rises immediately while closed-won revenue shows up later. Efficiency can look worse for one to three quarters depending on sales cycle length. Track efficiency alongside pipeline coverage and win rate, and separate ramping rep cohorts from fully ramped reps.

Sales efficiency is a fast, directional indicator that links spending to new ARR with a lag, usually at the quarterly level. CAC payback is unit economics: how many months of gross margin it takes to recover acquisition cost. Use efficiency for budget pacing, and payback for profitability and funding strategy.

Yes, but define spend and revenue motion clearly. If marketing drives signups and a small sales team converts upgrades, you can compute efficiency for the combined spend or split it by motion. The key is matching the right revenue (new and expansion ARR) to the teams actually responsible for it.